When Taquerias El Mexicano moved into my Little Havana neighbourhood, nobody thought it would last. That wasn’t because it was the first Mexican eatery en el barrio or because nobody wanted it; you’d have to be crazy not to want a taqueria in the neighbourhood. It wasn’t because it was bad. It was good. It was still good when I last visited in 2015. The locals didn’t think it would last because everything that opened in that spot closed after a short time. It’s hard to say why. It was on a busy street surrounded by mom and pop shops, including a shoemaker and dollar stores where my mother resolvia, a bakery that sold us our Cuban bread, pastelitos, and lottery tickets, a pharmacy, and a supermarket.

The pharmacy not only survived the opening the Eckerd-turned-CVS and Walgreens, two big pharmacy chains, it remodelled and expanded. It thrived thanks to its friendly staff that customers got to know, its colourful assortment of gifts, such as porcelain figurines accompanied by “you break it, you buy it” signs, and by selling medicines and medical supplies without prescriptions and at reasonable prices to old Cubans who needed them for their relatives in Cuba.

The small-chain supermarket managed to survive the openings of not one, but two Publix supermarkets. Whereas Publix had an “ethnic” food aisle and a few “ethnic” products throughout, el market catered entirely to the local Hispanic community. It was no frills and shopping was not always a pleasure there, but you could always find what you needed and find it cheap. As an aside, my first job at the probably illegal age of 15 was as a cashier at that supermarket. Despite my poor math skills, I was an excellent cashier, fast and precise. I retained the bagging skills and chide my partner every week for trying to pack hard items in the same bag as the bread. My mother and sister worked at that supermarket too, as did the young man that my sister later married. I think his brother may have worked there too, and his ex-wife. I went on one sad date with a boy that worked there. He was named after a brand of tea. He was cute and sweet and there was a shy chemistry between us, but neither of us knew anything about dating. It was that kind of supermarket. It has changed hands once or twice, but it might still be.

Maybe it was because of bad management that nothing survived in the spot where Taquerias El Mexicano moved in, or bad luck, or a curse – un fukú, like the Dominicans say. Whatever it was, Taquerias El Mexicano overcame it. Not long after it opened, The Miami New Times, a free weekly, gave it a favourable review despite its being in a “dumpy” neighbourhood. Say what?

Growing up, I knew that rich people did not live in my neighbourhood. They lived on private islands and neighbourhoods with names like Coral Gables and Cocoplum, not anywhere with “Little” in its name. And I had no idea there was such a thing as “middle class”. People were either like my family or they weren’t. I didn’t know my neighbourhood was dumpy. I didn’t even perceive it to be dangerous. When a car was set on fire in the middle of the night, a gunshot was fired at a party, or a body was found on the steps of a local warehouse, well, that’s just life in Miami. I still walked to the pharmacy or to work at the supermarket. There were a lot of things I didn’t know.

Over the years, that dumpy neighbourhood has become as hot as the jalapeños at the taqueria.

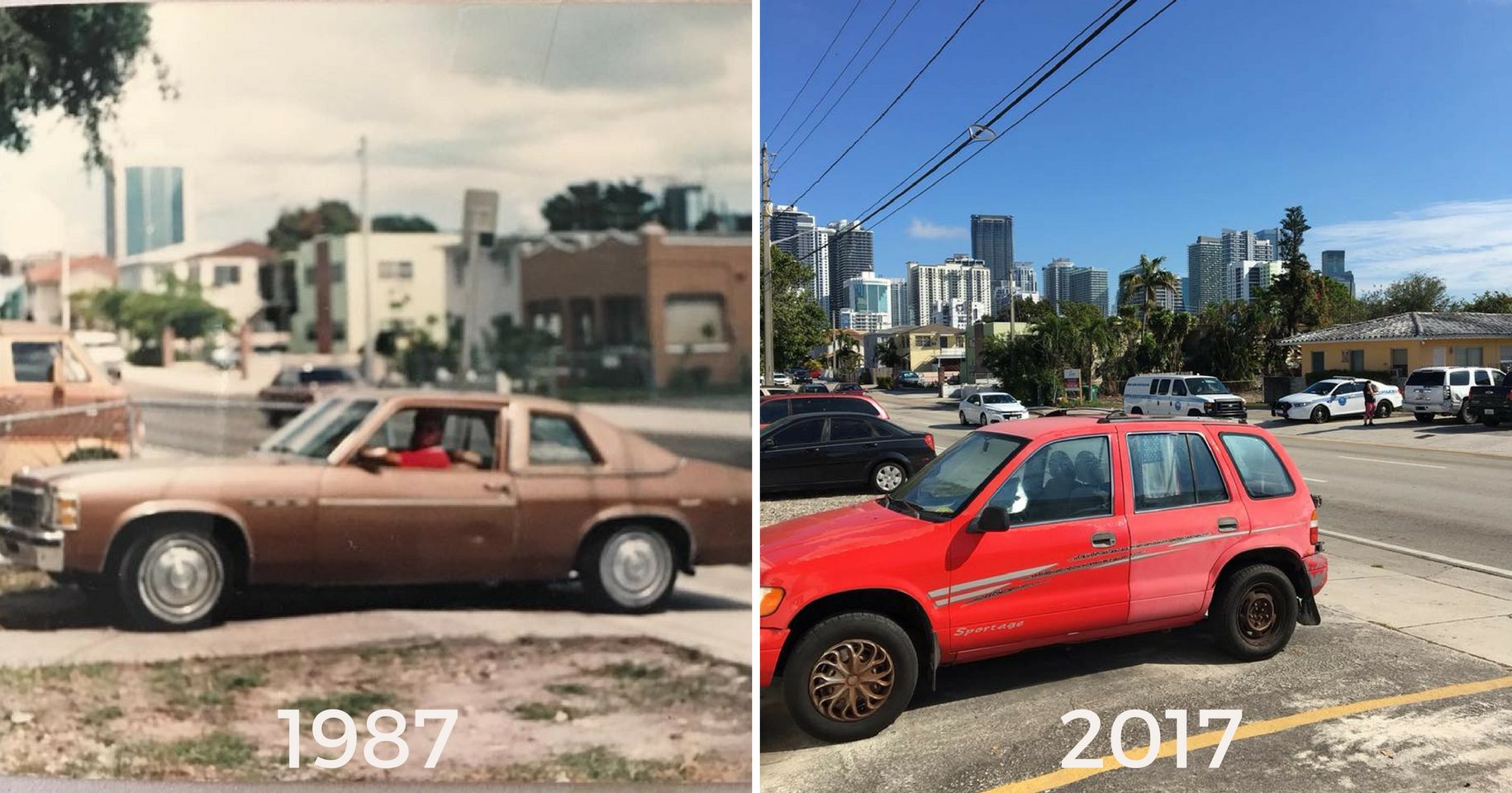

Recently, my partner and my sister were talking about their first cars. My sister dug up a photo to show him hers, a Pontiac LeMans that my father referred to as “el cadaver”. She was struck by how much the skyline has changed. In 1987, there was one tall building, which is now one of the shortest.

My family’s corner of Little Havana is close to the bay and the beaches. For years, my parents have rejected offers from developers while watching old homes go down and condos rise in their places. Last weekend, when I spoke with my mom over the phone, she told me the bakery is closing. It didn’t succumb to the competition. The owners accepted an offer on their valuable real estate.

“But where will you buy pan cubano y pastelitos?”

“Publix sells them,” she said.

“It’s not as good.”

“I know.”

Assimilation happens naturally. Case in point: my family.

After thirty-something years in the US, my parents, like many Cubans of their generation, do not speak English. They never learned. My family are refugees who arrived in the US with very little. You can get by in Miami just on Spanish and so they did, prioritising instead finding a safe place to live together, making ends meet, and taking care of a baby and a pre-teen girl. My father took English lessons for a time, at night, but abandoned them. He can kind of make do. He and my partner, who doesn’t speak Spanish, got on just fine. I suspect that my mother also speaks and understands more than she lets on, but may be embarrassed by her pronunciation. My sister and I, however, are bilingual. Her children struggle with Spanish. I wonder if the youngest, my 15-year-old nephew, will forget it. Over generations, immigrants are assimilated and the nooks and crannies they carved for themselves in the poor and dangerous corners of a city are gentrified. A dumpy neighbourhood becomes a goldmine. It was always gold to me.

Immigrants and expats take their place with them, but it’s only a version of it, one that is frozen in time and experienced through a unique lens. Whilst you live there, you’re like the frog that doesn’t realise the water he’s laying in is slowly being brought to a boil, but when you leave and return, the changes are striking. I can’t imagine that Miami will ever become a stranger. It takes a long time for a city to forget its history and flavours, but every time I visit, I know Miami a little less.