Recently, while searching online for modern resources about the Wheel of the Year in Wicca, I noticed something interesting. There’s no shortage of blogs and videos discussing the Sabbats, yet few describe the Wheel as a mythic cycle, where the changing seasons mirror the relationship between the Goddess and the God. This mythic framework was central to the books I read when I first learned about Wicca in the 1990s—works by authors like Doreen Valiente, Vivianne Crowley, Janet and Stewart Farrar, and Scott Cunningham—and later in my studies in Georgian Wicca. The Goddess and the God were at the heart of the Sabbats, shaping the rhythm of the Wheel.

In contrast, much of today’s content focuses on seasonal changes alone, omitting the divine drama. As one insightful Wiccan friend observed, this shift may reflect that many modern authors and creators are not Wiccan initiates, and their work often takes a broader, less tradition-specific approach. While modern practitioners frequently include deities in their celebrations, these choices don’t always reflect a cohesive cycle. For example, someone might invoke Hekate at Samhain and Brigid at Imbolc, which works beautifully in a polytheistic practice. As a polytheist myself, I appreciate this fluidity. However, I was searching for something specific—a Wiccan Wheel of the Year that presents the Sabbats as an interconnected story of the Goddess and the God.

When I couldn’t find what I was looking for, I decided to write it. This is only an introduction; much more could be said about the Wiccan Wheel of the Year. Let’s go!

The Wiccan Wheel of the Year is a modern creation blending folklore, anthropology, poetic myth, and contemporary innovation. It unites seasonal festivals from historical European pagan cultures, shaped by the mid-20th-century revival of Pagan spirituality and the need for a structured, meaningful ritual calendar.

Early influences: agricultural and solar cycles

The origins of the Wheel of the Year can be traced back to the agricultural and solar cycles observed by ancient societies. In Europe, many pre-Christian cultures celebrated seasonal festivals tied to planting, harvest, and the rhythms of the sun, such as solstices and equinoxes. Key examples include:

- Celtic fire festivals: Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane, and Lughnasadh marked critical points in the agricultural year. These festivals, celebrated in Ireland and Britain, were tied to pastoral and agricultural cycles and had strong spiritual significance.

- Germanic and Norse traditions: Festivals like Yule (Winter Solstice) and Midsummer were central to the Northern European calendar, celebrating light and darkness.

- Roman festivals: Festivals like Saturnalia and Lupercalia influenced the Christian liturgical calendar and, by extension, modern Pagan practices.

Origins: The foundations of Wicca

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, several key figures shaped the foundations of modern Wiccan thought, contributing ideas later woven into the Wheel of the Year:

- James Frazer: The Golden Bough (1890) popularised the idea of a universal cycle of life, death, and rebirth tied to nature and agricultural rites. It substantially influenced European literature and thought, inspiring Robert Graves, William Butler Yeats, H.P. Lovecraft, Jane Harrison, Sigmund Freud, Joseph Campbell, and others.

- Charles Godfrey Leland: In Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches (1899), Leland claimed to document the beliefs of Tuscan witches, including a myth of Diana (the Moon) and her brother Lucifer (the God of Light) giving birth to Aradia, a saviour and teacher of witchcraft. Though scholars question Leland’s claims, his work popularised the idea of a Goddess-centred spirituality connected to the Moon.

- Margaret Murray: In The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921), Murray proposed the existence of a pre-Christian fertility religion centred on a Horned God representing seasonal cycles of death and rebirth. While scholars discredited her theories, her vision influenced Wicca’s conceptualisation of the Horned God.

- Robert Graves: In The White Goddess (1944), Graves introduced the Triple Goddess as Maiden, Mother, and Crone, correlating with the waxing, full, and waning phases of the Moon. Though presented as poetic myth, many Pagans embraced his work as a historical framework.

The Sabbats: ancient roots and modern revival

As previously mentioned, the Wiccan Sabbats draw from diverse European pagan traditions, particularly those of the Celts, Anglo-Saxons, and Germanic peoples:

- Celtic fire festivals: Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane, and Lughnasadh marked significant points in the agricultural and pastoral year. They celebrated transitions in the natural world and spiritual interactions with deities and ancestors.

- Solar festivals: Anglo-Saxon and Norse traditions celebrated solstices and equinoxes, aligning their observances with the sun’s journey through the sky.

Gerald Gardner, the “Father of Wicca”, and Ross Nichols, who established the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids (OBOD), synthesised these traditions into an eight-fold calendar. Influenced and inspired by Frazer, Murray, and Graves, they framed the festivals around the balance of solar and agricultural cycles. By the mid-1960s, this calendar became known as the Wheel of the Year.

In the mid-1970s, American Pagan Aidan Kelly named Ostara, Litha, and Mabon, and Green Egg Magazine popularised them.

The eight Sabbats

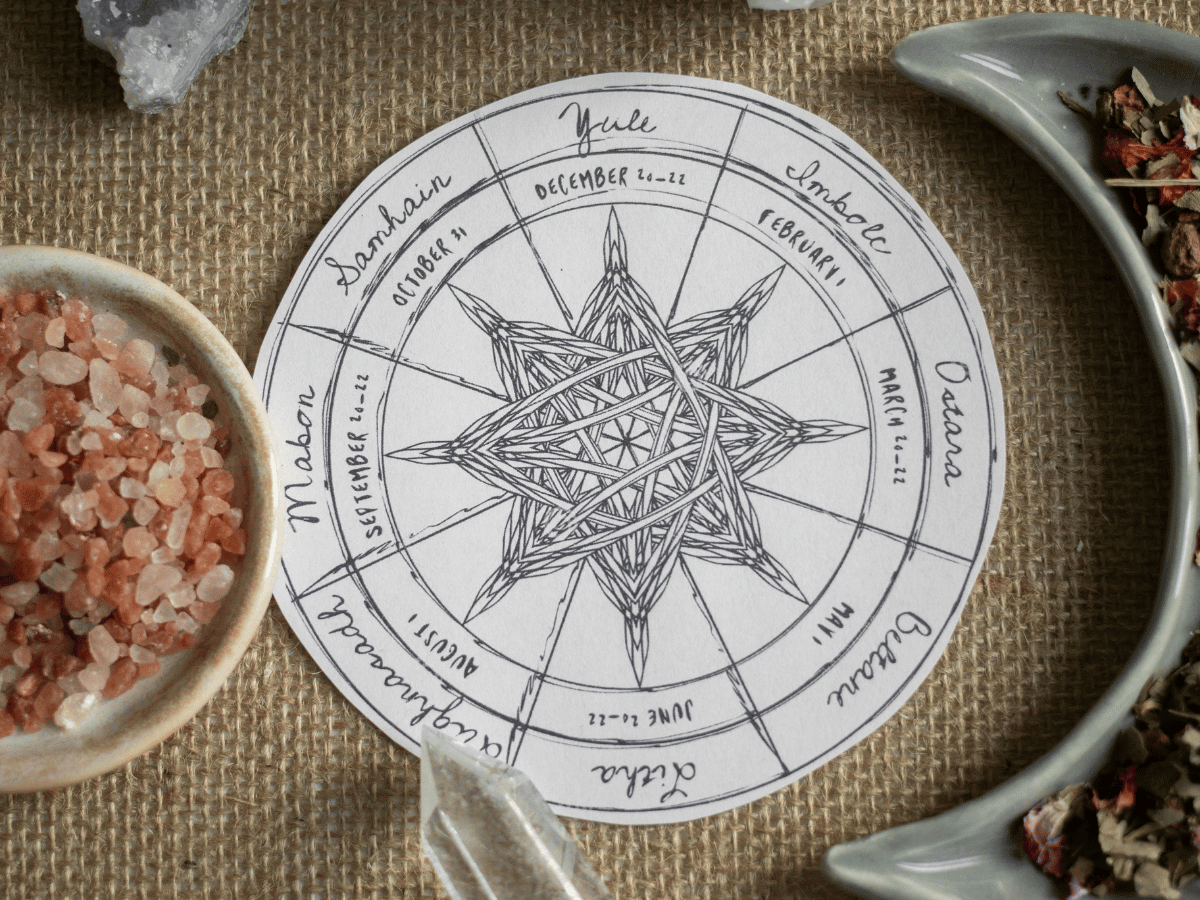

The eight Sabbats of the Wheel of the Year are:

- Winter Solstice (Yule): Rebirth of the Sun.

- Imbolc: Preparation for spring.

- Spring Equinox (Ostara): Balance of light and dark, renewal.

- Beltane: Fertility.

- Summer Solstice (Litha): Celebration of the Sun’s peak.

- Lughnasadh: First harvest.

- Autumn Equinox (Mabon): Balance of light and dark, second harvest, gratitude.

- Samhain: Third harvest, ancestors, endings, and the New Year.

The Goddess and the God in the seasonal cycle

Wicca envisions divinity as a duality: a Goddess, often associated with the Moon, fertility, and life, and a Horned God, tied to the sun, death, and renewal. Together, they symbolise the interconnectedness of all aspects of life and the cyclical nature of existence.

- The Goddess: Echoing Graves’ Triple Goddess, she embodies the Maiden, Mother, and Crone phases, each linked to different times of the year and lunar phases.

- The Horned God: Influenced by Murray’s theories, he is seen as a deity of the wild and the harvest, whose death and rebirth mirror the changing seasons.

A traditional Wheel of the Year

The Sabbats aim to align with the agricultural and seasonal cycles, reflecting the eternal dance between the Goddess and the God. Their story is a metaphor for the rhythms of life, death, and rebirth, guiding our spiritual connection to nature and its cycles. While a meaningful modern construct, the Wheel of the Year reflects a synthesis of diverse traditions and is not without its quirks or inconsistencies.

Winter Solstice (Yule)

In the deep silence of winter, the Goddess, in her aspect as the Great Mother, gives birth to the Sun God. He is a spark of hope and renewal in the darkest hour, heralding the gradual return of light to the world.

Imbolc

The first stirrings of spring awaken the earth. The Goddess, recovering from childbirth, rejuvenates into her Maiden aspect, embodying fresh beginnings. The God, now a child, grows stronger as the days lengthen, mirroring the rising light.

Spring Equinox (Ostara)

Light and dark are in balance, and life flourishes. The Goddess is a Maiden in full bloom, and the God is a spirited youth, eager to explore and embrace the world. Their energies are playful yet potent, sowing the seeds of future abundance.

Beltane

The sacred union of the Goddess and the God is celebrated as the earth bursts into vitality. Their love ignites creation, and the Goddess becomes pregnant, carrying the promise of the harvest. This is a time of passion, fertility, and joy.

Summer Solstice (Litha)

The God reaches the zenith of his strength, standing as the bright guardian of life. Yet, the longest day marks a turning point; he feels the first pull of the shadow, heralding the decline to come. The Goddess, radiant and abundant, oversees this shift, knowing the cycle must continue.

Lughnasadh

The harvest begins, and the God sacrifices his vitality to the land, ensuring the earth’s bounty. The Goddess, now heavy with child, acknowledges the God’s sacrifice, honouring the balance between life and death. The seeds of rebirth are sown.

Autumn Equinox (Mabon)

As light and dark balance again, God prepares to cross into the Otherworld. As the harvest queen, the Goddess gathers the fruits of their union. She mourns his impending departure but understands his journey is necessary for renewal.

Samhain

The God descends into the underworld, where he becomes the seed of rebirth within the womb of the Goddess. She takes on her (pregnant?) Crone aspect, the wise guardian of the mysteries, watching over the cycle as it begins anew. Together, they guide the transition into the quiet introspection of winter.

This cycle does not include other popular mythic elements, such as the Battle of the Oak and Holly Kings or the Wild Hunt, as incorporating more layers seemed forced and bloating.

An inclusive Wheel of the Year

The traditional Wiccan Wheel of the Year centres on the duality of the Goddess and the God, representing the interplay of masculine and feminine energies. As such, the framework is inherently heteronormative. The cycle, as it has been passed down, often presents a binary relationship between two deities, which may not resonate with all practitioners. While this mythic structure holds deep meaning for many, it can feel limiting for others.

As a straight ciswoman with a complicated relationship with the gender binary, I recognise that I am not the best-equipped person to reimagine a more inclusive Wheel. Practitioners with lived experience—such as Deborah Lipp, Yvonne Aburrow, and Enfys J. Book—are already addressing this. Nonetheless, I couldn’t spend so much time contemplating and writing about this and ignore inclusivity.

A more inclusive reinterpretation of the Wheel focuses on key principles that transcend gendered roles. Rather than framing the mythic cycle around the Goddess and God, we can centre it on archetypal energies—such as creation, transformation, and renewal—that reflect the dynamic and nonlinear relationships between forces. These energies do not exist in isolation or binary pairings but in the interdependent interplay of many forces. Creativity and growth emerge from these interactions, not from fixed roles.

This reinterpretation also encourages practitioners to engage with the archetypes in ways that resonate with their own identities and experiences. For example, fertility might represent artistic expression, collaboration, or personal healing rather than reproduction. The energies within the cycle are fluid and multifaceted, existing in all beings and transcending form and identity. Each person embodies aspects of the archetypes at different times, embracing the fluidity and multiplicity of life’s cycles.

Winter Solstice (Yule)

From the stillness of winter, a spark of potential is born, the Child of Light. This being represents hope, resilience, and the promise of renewal. The Great Source (a nurturing, creative force) holds the spark within its embrace.

Imbolc

The first stirrings of spring bring awakening and the promise of growth. The Earth Spirit, embodying renewal and curiosity, stretches alongside the lengthening days. This spirit’s energy encourages us to seek new beginnings and nurture emerging possibilities.

Spring Equinox (Ostara)

The energies of exploration and emergence flourish at the balance of light and dark. The Divine Seeker emerges, neither bound by form nor expectation, embodying curiosity, play and the potential for connection. Their journey mirrors the sprouting seeds and budding flowers.

Beltane

The celebration of connection and creativity honours the sacred dance of energies. The Creative Forces meet in joy, symbolising the power of relationships—whether with others, nature, or oneself. Fertility is understood as creative potential manifesting in myriad forms.

Summer Solstice (Litha)

At the peak of the sun’s strength, the Radiant One embodies vitality and generosity. This energy reaches outward, celebrating abundance and shared growth. Yet, within this brightness, the shadow begins to stir, a reminder that cycles must turn to sustain balance.

Lughnasadh

The Bearer of the Harvest offers their energy back to the land. This being represents the principle of transformation, teaching us that endings and sacrifices can seed future growth. The Earth Spirit, now a guardian of change, honours this offering.

Autumn Equinox (Mabon)

As the light wanes, the Gatherer appears, carrying the fruits of labour and reflecting on the gifts of the cycle. They guide us to gratitude and acceptance, preparing us for the inward journey ahead. The balance of light and dark reminds us to embrace transitions.

Samhain

The Veiled One, keeper of mysteries, steps forward as the cycle begins its rest. This being represents wisdom, introspection, and transformation. The spark of potential returns to the Great Source, ready to start anew. In this time of stillness, we honour the unseen connections that sustain us.

Hopefully, this model inspires something.

The Wheel of the Year offers a way for modern Wiccans to connect with nature’s rhythms, the cycles of life, and spiritual renewal. It has been adapted globally to fit different climates and cultural contexts, reflecting its flexible and inclusive origins. While modern in form, this structure honours ancient traditions and provides a bridge between historical practices and contemporary spiritual needs. It continues to evolve as Wiccans and other Pagans reinterpret its significance in modern times.