After last month’s article on Ochún, the orisha of beauty, love, and sexuality, I received questions about Lukumi, initiation, how I got involved in the religion, and how you could too. In this article, I share my journey to the orishas, to Lukumi and, hopefully, answer some of your questions along the way.

First, there are a few important things to note. Lukumi is only one of several African diasporic religions. For complex historical reasons rooted in colonialism and slavery, it is a closed tradition that is primarily orally transmitted. This means that you are born or accepted into it and, until you are, you will not learn the bulk of its beliefs, customs, and rituals. Lukumi has no central authority, and the centres of learning and practice are typically the private home of a priest or priestess. Consequently, for this and other reasons, Lukumi shows a great deal of variation.

For example, the order in which I have undertaken the ceremonies makes sense in light of how it unfolded, but it is a bit unorthodox. My first house was traditional, private, and highly engaged with the community. My current house is a little more relaxed, open, contemporary, and far less engaged with the broader community. Both are family traditions, but different lineages and priesthoods of different orishas.

What follows is a summary of my limited experience with Lukumi. I will not disclose the details of the rituals. It would be disrespectful and inappropriate to do so.

The basics of Lukumi

Lukumi, also known as Regla de Ocha and very commonly as Santería, is an African diasporic religion that developed in Cuba. It is understood to be a syncretism of:

- Cuba’s indigenous Taíno religion;

- the traditional religion of Yorubaland (present-day Southwest Nigeria), where Cuba’s enslaved people were brought from;

- Roman Catholicism, where we get the common name of Santería (a reference to saints);

- Spiritism, which is used in ancestor veneration and spirit communication.

Lukumi is a religious stew, and it’s hard to figure out the roots of a particular belief, custom, or ritual. Some elements, such as statues of Roman Catholic saints, are clear, but many are not.

Some people assert that Lukumi is a monotheistic religion with the transcendent creator deity Olodumare at the centre and the orishas as his emissaries, similar to the Abrahamic God and angels or saints. Orishas are not gods, but you could argue that they are treated like deities, and the religion feels polytheistic.

Lukumi is a prescriptive, community religion with lineages organised in houses; there’s no central authority. It is also a very secretive religion, and it is passed on orally for the most part. You don’t have to learn everything, and there’s no expectation that you ever will. There are priests, diviners, costume and jewellery makers, drummers and singers, shop owners, people who raise animals, sacrifice animals, and so forth, with overlap. Through divination and direct contact with the orishas (via their possessed priests), you are informed which orisha you would be a priest of, what rituals and initiations you should undergo, what role you might play in the religious community, what standards of behaviour you should keep, and more. For example, the children of Obatala are generally forbidden to consume alcohol, and I was advised against wearing yellow (I explain below).

In terms of other beliefs, we believe a spiritual-mystical energy or power, called ashé, is found in everything to varying degrees, and practitioners seek to fortify this energy. Ancestor veneration is very important, as are standards of behaviour, healing, and fulfilling our higher purpose. Luz y progreso (“light and progress”) is a common expression in the community.

My journey to the orishas and Lukumi

I was born in Havana, Cuba, and raised in South Florida, but my immediate family is Roman Catholic and did not practice Lukumi. I became interested in Wicca and Witchcraft long before coming to Lukumi.

Fresh out of college in my early 20s, I started working at a book store and became friends with a few people interested in Witchcraft. We not only became friends, but we also practised basic rituals. One of them later joined a coven with me (and we’re both still friends and coven mates). Another one came from a Cuban family of Lukumi practitioners, but he was not fully initiated. Together, we moved more in that direction. His older brother and sister became my teachers and guides into the religion, figures commonly referred to as godparents (an example of the Roman Catholic influence). It was a house of Ochún.

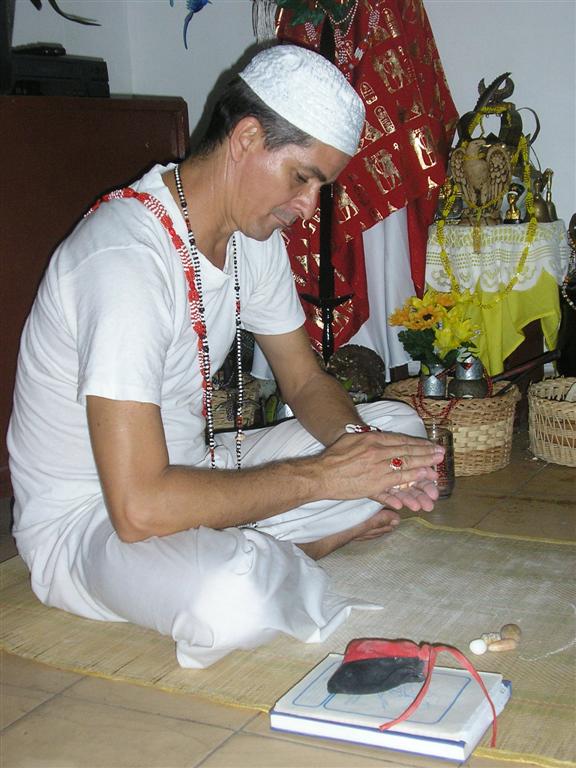

El registro con Eleguá (2008)

In 2008, I met with an oriaté, a priest with expertise in divination, for a general consultation with Eleguá. This messenger orisha opens and closes doors, including communications with other orishas.

As I mentioned previously, Lukumi is a prescriptive religion. You don’t choose your tutelary spirit and some aspects of your spiritual path. You have a destiny, which is revealed to you by the orishas through their trained priests.

The divination is performed via the diloggún, cowrie shells, usually about 16, with a possible 256 patterns of interpretation with various stories attached to them. It’s complicated, and not all priests read the diloggún.

The oriaté spoke in Spanish and Yoruban. His partner wrote it all down, and they, together with my godparents, helped me understand it. Eleguá warned me about health problems regarding blood, among other things, and the oriaté said I would likely be led to initiate. They told me that Ochún and Yemaya, the orisha of the ocean, love me very much.

Notably, Ibú Kolé spoke and told me not to wear yellow. The elders explained that Ibú Kolé is a form of Ochún associated with mud and the vulture. She is destitute and owns only one white dress, which has yellowed from washing it every day in the river. Seeing me in yellow reminds her of this and saddens her.

Finally, Eleguá advised me to receive the guerreros (warriors) and Olokun, the mysterious orisha of the ocean depths.

There is another simpler form of divination called obi, a kind of yes/no divination with the coconut. It’s usually done at the end of a ritual to verify whether an orisha is satisfied.

Los guerreros (2008)

Just two months later, I underwent a ceremony and received the guerreros. The warriors are Eleguá, Ogún, Ochosi, and Osun.

Eleguá opens and closes the doors to help you remain on the right path. He is represented in various ways, including a cement head with cowrie shells for features. My godfather privately determined the form of my Eleguá, which is a beautiful piece of coral. This and the advice to receive Olokun have always made me assume a connection with Yemaya.

Ogún is the divine blacksmith, the spirit of iron, and human effort. With his machete, he clears the path for you. Ochosi is the divine hunter associated with justice, who points you in the right direction. They are received inside a black cauldron that holds their implements and other sacred items. Osun is the guardian of our heads, a custodian, and watchman represented by a rooster atop a metal cup fringed with four little bells symbolising the four directions.

The ritual was in two parts (and was delayed by a hurricane). It involved a lot of cleansing, prayers, imbuing the implements with the spirits of the orishas, feeding them, making offerings, divinations, and learning about them, their care and keeping. The guerreros are divine guardians who protect us and keep us on the right path.

La bajada (2009)

Nearly a year later, in 2009, I underwent divination referred to in Spanish as la bajada (“the lowering”), which is to discover your angel de la guardia (“guardian angel”). There’s that Roman Catholic influence again. The orishas are not angels, and they’re not saints. So, I don’t use this language and prefer to say my tutelary orisha, my patron, or the orisha that owns my crown, and I would become a priestess of.

Once again, I met with an oriaté who used the diloggún, cowrie shells. He asked. Obatala? No. Chango? No. Yemaya? No. Oshun? No. There was some surprise and confusion. The oriaté decided to start at the beginning. Eleguá? No. Ogún? Yes!

Elekes (2012)

In 2012, just days before leaving the U.S. for Australia, I received the elekes, or collares, the beaded necklaces of the orishas. By this time, I had a new godparent and joined a house of Yemaya, which I’ve remained at.

This important ceremony formally establishes a relationship with the orishas and places you under their protection and influence. Traditionally, there are five necklaces: Eleguá, Ochún, Changó, Yemaya, and Obatalá, and I received a sixth: Ogún.

It was a lovely, calm, and simple ceremony that I had to undergo before receiving Olokun. Received elekes and guerreros changed my status within the religion from aleyo (“stranger”) to aboricha (“one who worships the orisha”), and I am considered half-initiated or halfway to being initiated (medio-asiento in Spanish, literally “half-seated”).

Olokun (2015)

During a visit to South Florida in 2015 and just a few days before flying back to Melbourne, I received Olokun, the mysterious, androgynous orisha of the depths of the ocean.

Olokun brings healing, wealth, and stability to the initiate. This ceremony involved more planning, supplies, people, and offerings and was the most expensive.

Kariocha (TBD)

To be fully initiated into Lukumi, I must undergo a massive ritual known by many names, including kariocha, making ocha, making santo (saint), or asiento (“seating”). It’s two days of preparatory rituals and a seven-day ceremony. It involves divinations, sacrifices, purifications, the “seating” of your orisha, receiving many sacred items, and a public celebration. It varies depending on which orisha it is, but they are all elaborate and expensive.

After the ceremony, you are an iyawo, which means “slave of the orisha” or “bride of the orisha”, or both. You enter one year of restrictions. Iyawos typically wear white and have their heads covered for the year. After this period, there is another ceremony, and you can conduct rituals and participate in the initiation of others.

You become a priest of one orisha (and discover their specific form), contributing to what you can and can’t do within the religious community. You also learn the identity of your secondary orisha and a whole bunch of life matters through major divination.

Other initiations

Before and after kariocha, you may receive other initiations. For example, you might receive the Ibeji, the sacred twins, or Olokun, like I did.

Lukumi is a closed tradition, but you are still welcome

This is a summary of my limited experience with Lukumi, and it is the tip of the iceberg. I will revisit this subject in future articles.

Lukumi is a closed tradition, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it isn’t open to you. Creyentes (“believers”), that is, practitioners, can be found all over the world, even here in Australia (and I don’t just mean me). Most do not identify as Pagan nor associate with them and are generally suspicious of outsiders.

In South Florida, there is little to no controversy around race and ethnicity and participation in Lukumi. Cubans are ethnically mixed and may appear racially white, black, and every shade in between. At a big Lukumi event in Miami, you would see a range of people, even white Americans. I have found the same to be true in Australia.

We should not ignore race, ethnicity, colourism, privilege, and cultural appropriation issues. If you are a white person, please reflect on why you are so interested in this religion, this religión de los negros–the religion of the black people, of the enslaved people. What do you think you will find here that you can’t find in the spiritual traditions of your ancestors? This doesn’t mean that Lukumi is off-limits, but if you feel driven to explore this religion, know that it will require levels of patience, humility, and respect not often seen in contemporary Paganism.

Thank you for sharing your personal story as it helps the neophytes to this tradition understand better. There are many commonalities shared with other ATR’s and personal stories like this helps sort them out some

Thank you, Diana! I appreciate you taking the time to read this and share your thoughts. I also enjoy reading personal ATR stories.

Hello thank you for sharing your story. Im in a similar place in my life where I want to start my journey but I’m not sure where to start. I used to live in Florida but now I’m in colorado. Reading your experience gives me hope that ill find my way soon.

Thank you for your comment. Beginning the journey can feel uncertain, but you’re not alone in that. I’m glad my experience offered some encouragement, and I trust you’ll find the next steps that feel right for you.