I am dedicating November to the Minoan Snake Goddess. Here’s a short introduction to her and her origins and a brief look at contemporary Minoan-inspired Pagan practices and my devotion.

In high school, I came across a yellow book called When God Was a Woman by Merlin Stone, which blew my teenage mind. The figure on the cover was the Minoan Snake Goddess. She struck me, and I’ve remained fascinated. Over the years, she has become the goddess I associate with an important symbol in my life, the serpent.

November is my birth month. It’s a happy and celebratory month, but as the year comes to a close, it’s also when I start to reflect on the past year and plan for the next one. November is my month of birth and regeneration, which I associate with the serpent, and no other goddess represents that energy for me more than the Minoan Snake Goddess.

Who is the Minoan Snake Goddess?

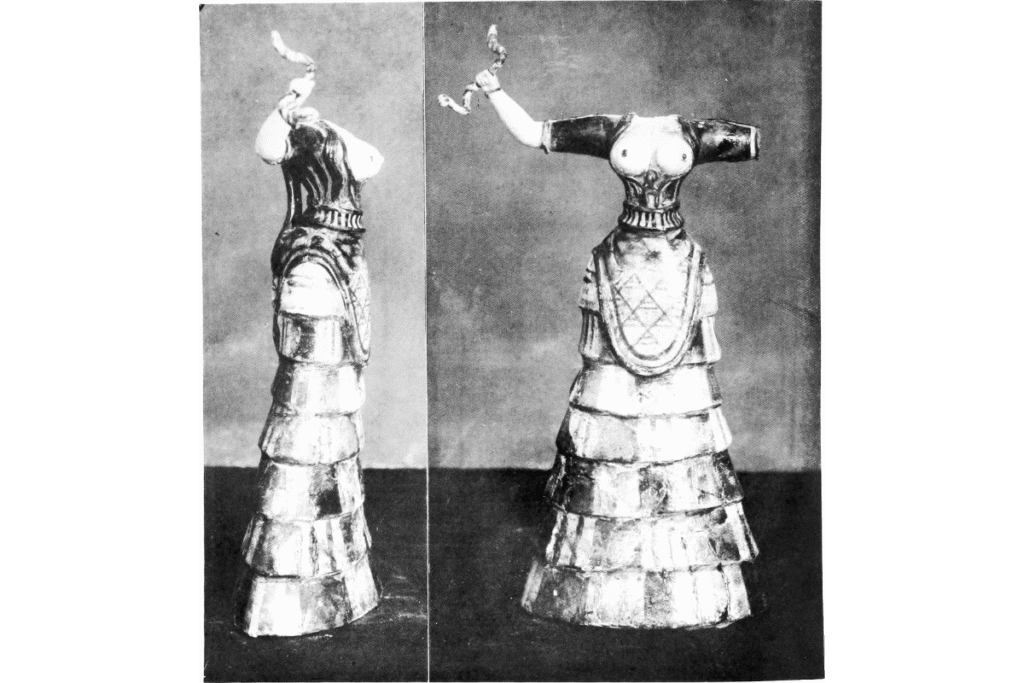

“Minoan Snake Goddess” refers to two figurines found in the Minoan palace at Knossos on the Greek island of Crete in 1903. Both were incomplete, and the figurines we know and love today are “restorations”. We use “restorations” loosely because Arthur Evans, the English archaeologist who discovered the palace, took some creative and romantic liberties.

Evans called the larger of the pair a Snake Goddess and the smaller a Snake Priestess though the latter is the iconic one best known as the Minoan Snake Goddess. We don’t know if these figures represent a goddess or a priestess.

Who were the Minoans?

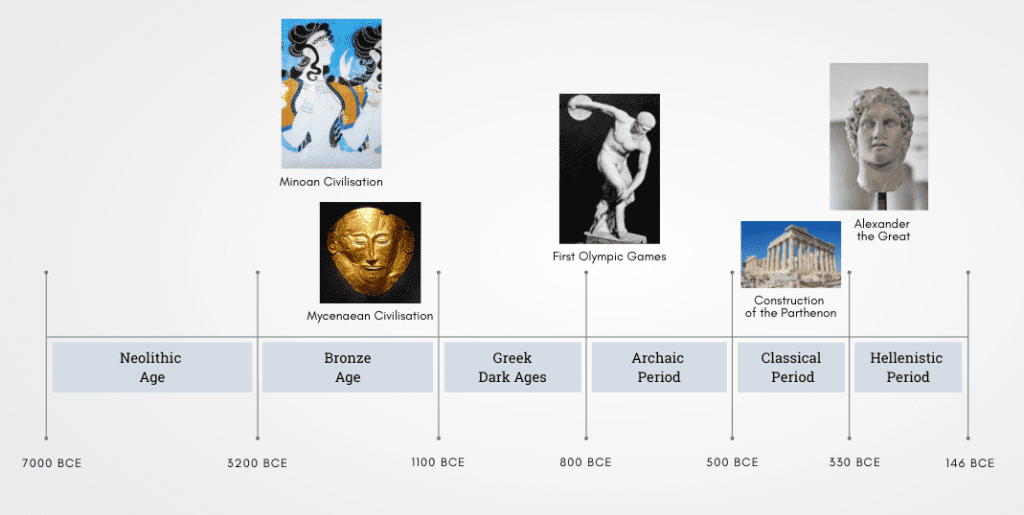

The Minoan civilisation was a Bronze Age Aegean civilisation on Crete and other Aegean islands from about 3500 BCE to 1100 BCE. With their impressive architecture and sophisticated art, the Minoans represent the first advanced European civilisation. I made this rough timeline to show where the Minoans sit in the history of Ancient Greece.

Early archaeology painted the Minoan civilisation as a peaceful and matriarchal society, and feminist theologians and the Goddess Movement ran with that, but there are no definitive conclusions. There seems to be no evidence of a Minoan army. Still, archaeologists debate the functions of fortified centres, whether scenes in art depict warfare or sports and rituals, and whether daggers and swords were weapons, mundane tools, or ritual objects. This doesn’t necessarily indicate a pacifist society; the Minoans had a powerful navy but didn’t seem to have been expansionists. They were agricultural, mercantile, and engaged significantly in overseas trade, perhaps dominating trade in the Mediterranean.

Many historians and archaeologists are sceptical about the Minoans having been matriarchal, but some think they were. Women figure predominantly in art and religious artefacts and are represented very differently from men. Women are portrayed with light skin, clothed and in elaborate clothing, and men are depicted with dark skin and wearing little. Female figures assumed to be goddesses or priestesses appear seated and flanked by other people and mythical creatures; there aren’t any representations of a seated male.

Many aspects of Minoan life, governance, and religion remain unclear. We don’t even know what they called themselves. “Minoan” refers to the mythical King Minos of Knossos, a figure in Greek mythology. German classical historian Karl Hoeck used the term in a book in 1825, Evans applied it, and it stayed with us.

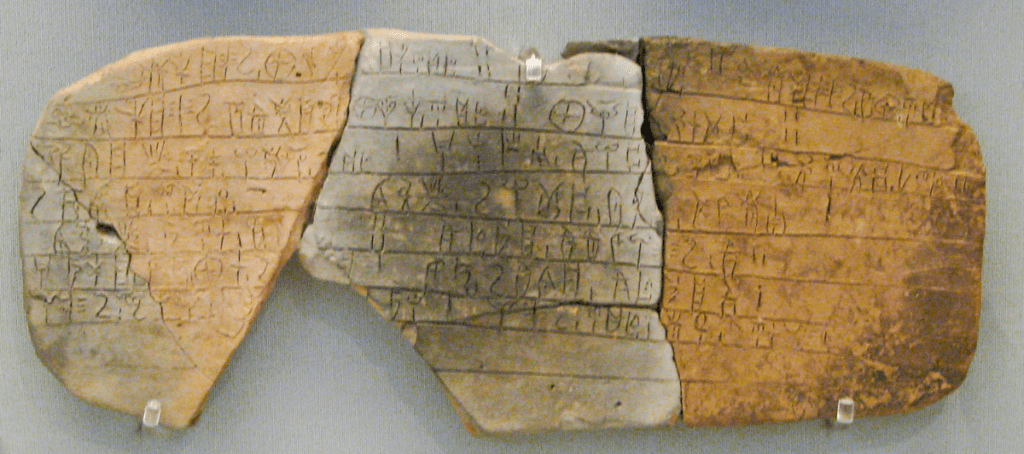

The Minoans had writing: Cretan hieroglyphics and Linear A script, but neither has been deciphered. Linear B, a script used in Mycenaean Greek, the most ancient form of the Greek language, is descended from Linear A. Based on the research of American classicist Alice Kober, self-taught linguist Michael Ventris deciphered Linear B in 1952. It seems to have been chiefly used in administrative contexts. For example, the clay tablet shown here contains information on the distribution of bovine, pig and deer hides to shoe and saddle-makers. Nevertheless, Linear B gives us some insights into Linear A.

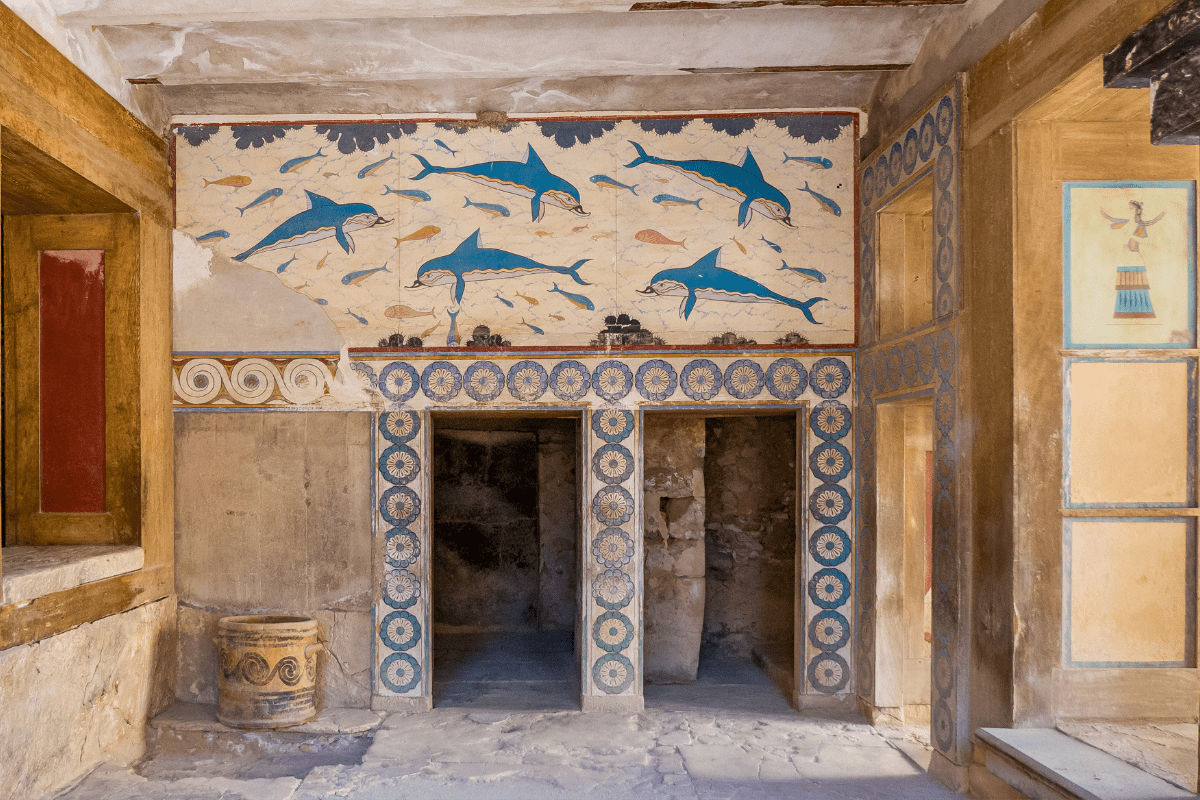

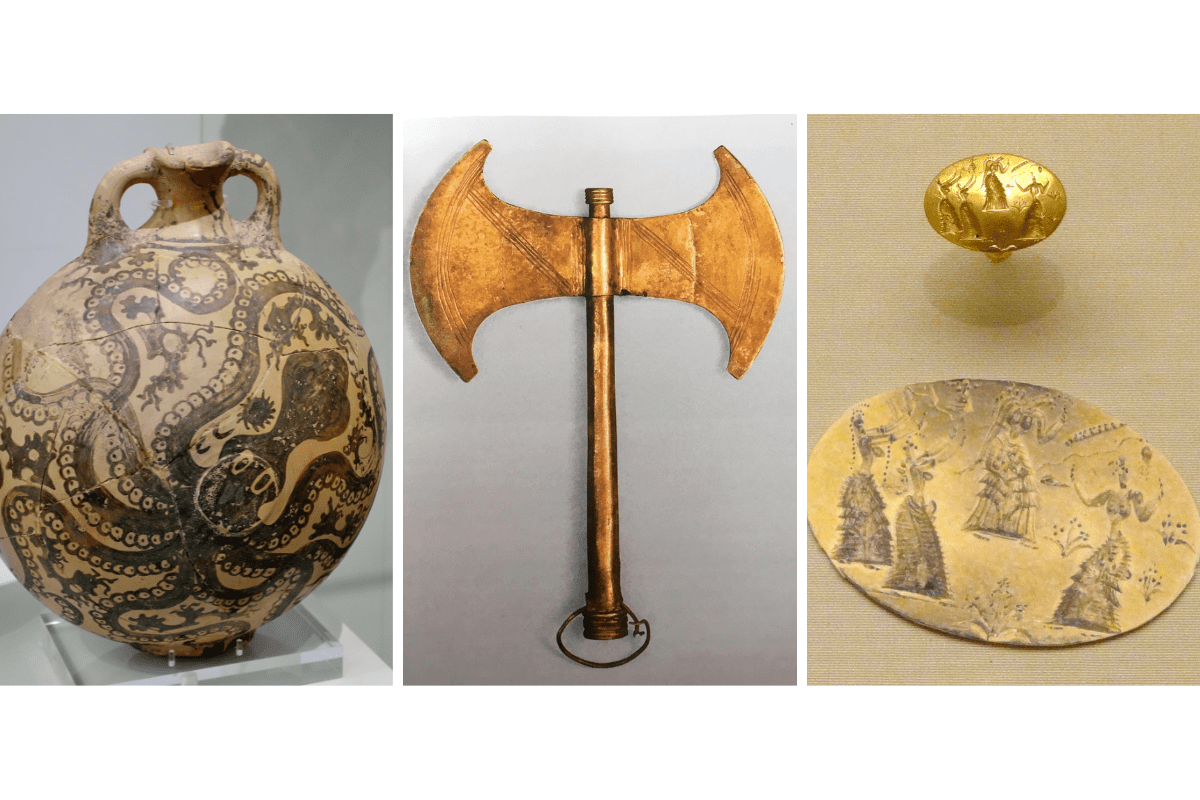

So, how do we know what we know about the Minoan civilisation? We know the Minoans primarily through archaeology–the mazelike palaces and villas, sacred places, burial sites, tools, art such as their vibrant frescoes, pottery and metal vessels, weapons, jewellery, impression seals, and the genetic study of Minoan remains.

What about the Minoan religion?

Arthur Evans thought that the Minoans worshipped a mother goddess, but the current view is that they had a pantheon with a central (possibly solar) goddess and a younger male figure, perhaps a consort or son. The Goddess was associated with animals and mythical creatures, and priestesses served her. Men also had roles as priests or priest-kings.

Minoan goddesses include Dyktynna, a goddess of mountains, and Eleuthia (Eileithyia), a goddess of childbirth connected with caves. Hungarian scholar Károly Kerényi and Robert Graves theorised that Ariadne, known in Greek mythology as a princess of Crete, was an important Minoan goddess. The early twentieth-century Swedish scholar Martin Nilsson proposed that Athena was originally the Minoan snake goddess.

Atana Potinija (Mistress Athena) appears in a Mycenaean Greek inscription at Knossos in the Linear B tablets. Virginia Hicks, a scholar studying Linear A, agrees that the Mycenaeans adopted the main goddess of the Minoan pantheon. She writes that Atana Potinija is the Mycenaean attempt to translate the name of the Minoan goddess and points to Atano Djuwaja in Linear A, which, she claims, means Sun Goddess.

Important cult symbols include the labrys, or double-headed axe, and bull’s horns. Minoan palaces and villas were multifunctional and religious rituals may have taken place there. There were also rural peak sanctuaries and sacred caves. The Minoans practised animal and possibly human sacrifice, a controversial subject among archaeologists.

What happened to the Minoans?

A volcanic eruption followed by a massive tsunami devastated the coast of Crete and destroyed many Minoan settlements. These natural disasters triggered a crisis, but the end of the Minoan civilisation ultimately came from conquest. By about 1450 BCE, the Mycenaean Greeks controlled Crete and adapted Minoan culture, religion, and art.

Minoan Neopaganism

It’s impossible to practice a reconstruction of the Minoan religion; we need to learn more about it, but the scholarship of the early 20th century strongly influenced the Goddess Movement and inspired contemporary practices.

In response to the heteronormative approaches of Traditional Witchcraft in the 1970s, Eddie Buczynski, a prominent Wiccan and gay rights activist, founded the Minoan Brotherhood, “a men’s initiatory tradition of the Craft celebrating Life, Men Loving Men, and Magic in a primarily Cretan context.” The Minoan Brotherhood adopted a Gardnerian framework and blended it with Cretan and Mycenaean elements. Lady Rhea of Magickal Realms and Lady Miw-Sekhmet founded and led its sibling path, the Minoan Sisterhood, for lesbian and bisexual women.

In 2014, Pagan artist and author Laura Perry created a Facebook group that led to the founding of Modern Minoan Paganism. This revivalist tradition has developed a pantheon and sacred calendar. Perry is also the author of Labrys and Horns and creator of the Minoan Tarot, both of which I recommend. Ellen Lorenzi-Prince, creator of the Dark Goddess Tarot and Tarot of the Crone, also created a Minoan Tarot.

My religion of one

My religious practice derives ideas and methods from historical, polytheistic paganism, the Goddess movement, Wicca, Lukumi, shamanic practices, tantra, and Tibetan Buddhism. My pantheon is diverse, but the serpent appears throughout.

The Minoan Snake Goddess is the figure I connect most strongly to serpent symbolism: regeneration, guardianship, and wisdom. This may be ahistorical; it’s an area of my practice that relies more on personal gnosis. My approach is devotional. I build an altar for her, make daily offerings, pray, and meditate. I don’t recall ever invoking the Minoan Snake Goddess in my magick. This may change. One of the benefits of the dedicated month is the opportunity to revisit the structure of my practice, expand it, and deepen my knowledge and relationship with the goddess.

Hey thanks for this!! I recently had a reading and am heavily connected with the Minoan Snake Goddess so in doing research I came across this and it’s been the most helpful! So again thank you!

I’m very glad to hear that, Jordan! Thank you for reading and commenting.