Hekate is an important goddess in my pantheon. I have a shrine dedicated to her and observe the monthly Noumenia. I dedicate October to Hekate, a month to study her more closely and deepen my connection.

In 2023, I was privileged to visit Stratonikea and Lagina in Türkiye and another sacred site associated with Hekate: Elefsina in Greece.

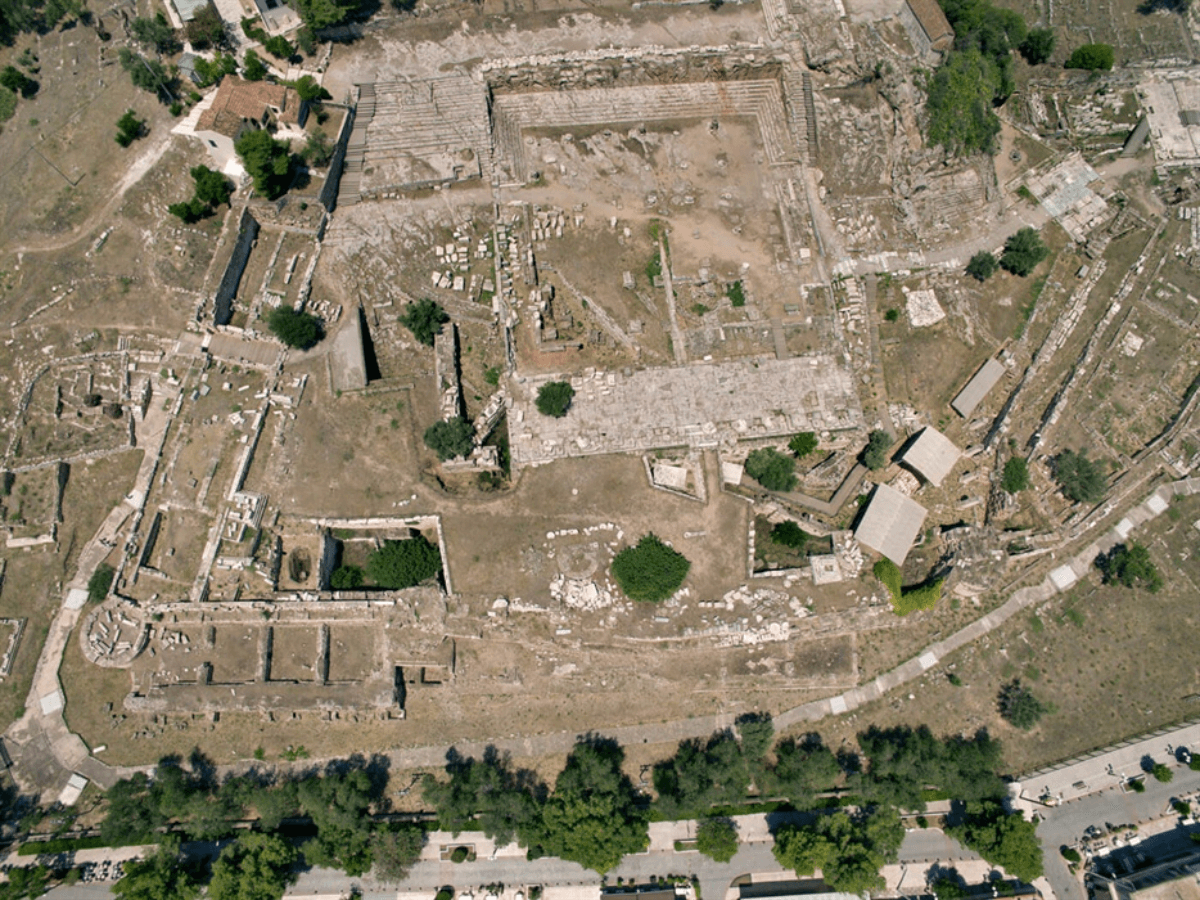

Elefsina, or Eleusis, is a small suburban city in metropolitan Athens. It’s about an hour’s drive from central Athens. It is the birthplace of Aeschylus, the father of Greek tragedy, who wrote 70-90 plays, of which only seven survive in complete form, including the Oresteia. Today, Elefsina is a major industrial centre with the largest oil refinery in Greece; you can’t miss it as you drive into the city. Still, beneath the surface, Elefsina holds the secrets of one of the most important religious ceremonies in Ancient Greece—the Eleusinian Mysteries.

The Eleusinian Mysteries were secret religious rites held annually in ancient Greece. They centred around Hades, the god of the Underworld, abducting Persephone from her mother, Demeter. These rites offered participants knowledge of the afterlife and the cycle of life and death and were among the most significant spiritual rituals of the time. Initiates, sworn to secrecy, underwent a series of ceremonies over nine days, culminating in an experience of divine revelation within the Telesterion, the grand hall at the heart of the Mysteries.

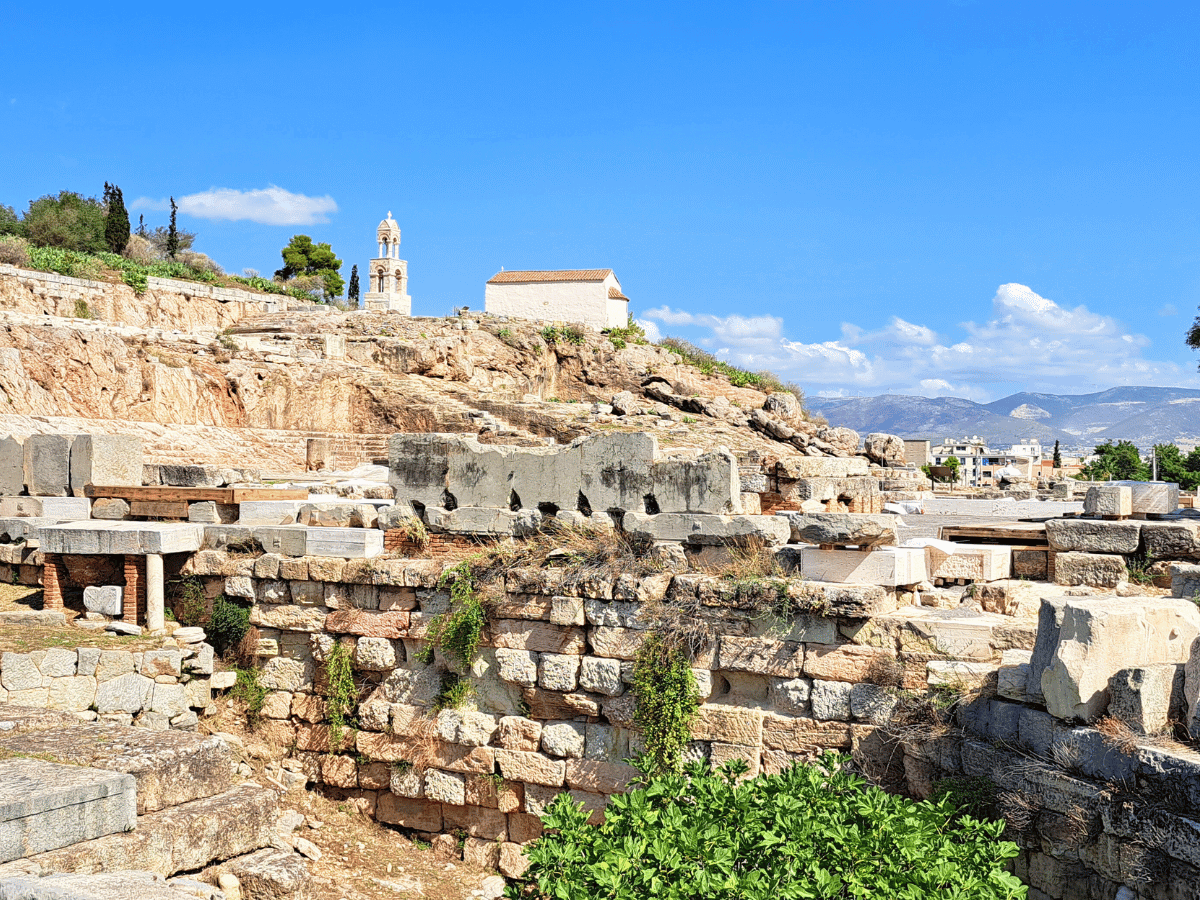

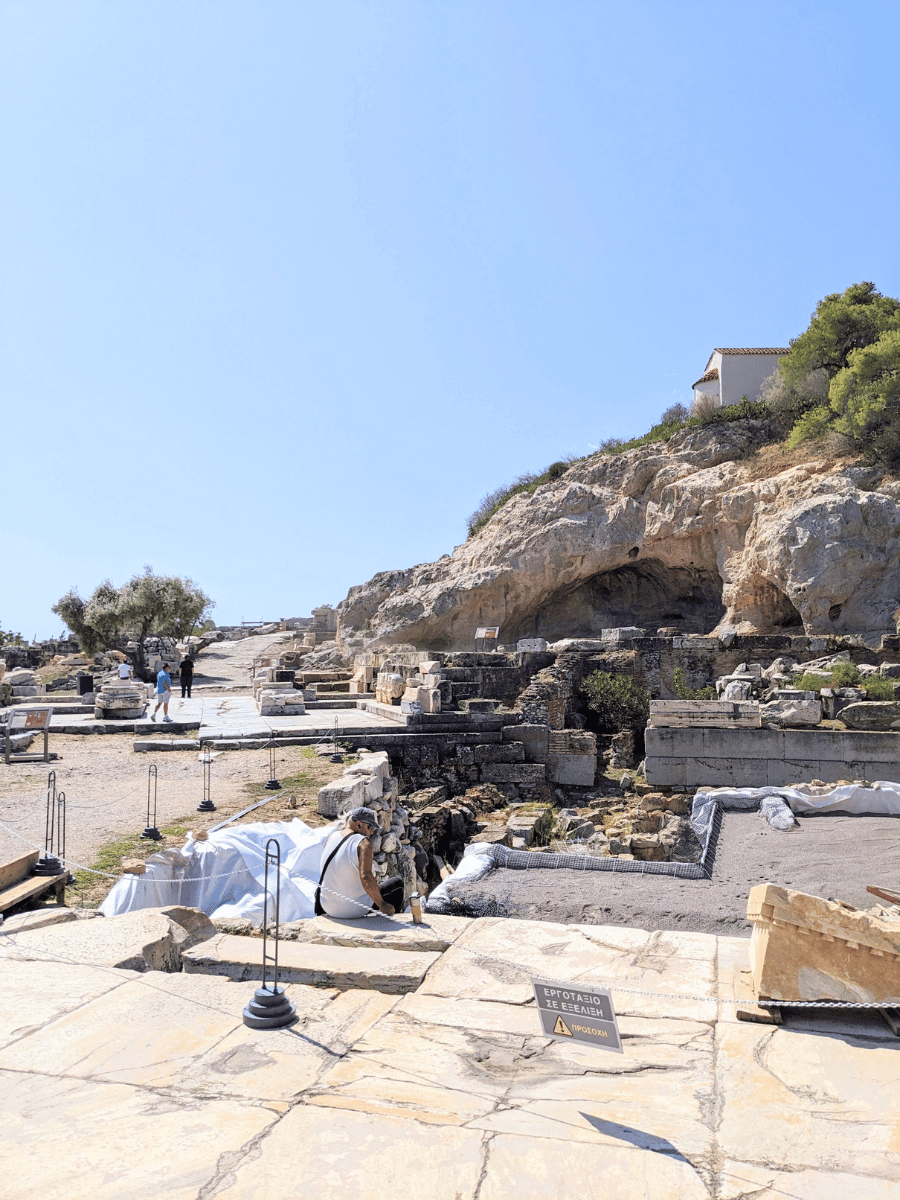

Visiting Elefsina with the anticipation of stepping into the world of the Eleusinian Mysteries brought a unique mix of excitement and reverence. The thought of walking in the footsteps of ancient initiates stirred my Pagan heart. However, arriving to find a city dominated by industrial complexes and the site in crumbling ruins was a far cry from the idyllic beauty many associate with Greece.

There’s a poignancy to seeing a place once so sacred now weathered and worn. The fragmented ruins evoked melancholy as they sat against an unremarkable townscape. The Mysteries have faded, but history lingers in the ruins, and the stones carry the whispers of the gods.

My husband and I arrived shortly after the site opened for the day. We were the only ones there and enjoyed having the site mostly to ourselves.

Exploring Eleusis

The Roman Court is in front of the main entrance. It has steps, and we walked up and past the Northwest Portico and Eschara (Grate), a platform where a temple of Artemis and Posideon once stood, the West Triumphal Arch, the Greater Propylaea, the Kallichoron Well, Fountain, the East Triumphal Arch, and the Baths, stepping foot onto a path around the site.

I didn’t take many photos here because I was overcome, and there wasn’t much to photograph. It was rocks, pieces of something once grand, and few identifying signs.

I noticed a man following us as we walked along the Periclean Fortification, the walls that enclosed the Sanctuary. Assuming he was one of the site’s guardians, I called to him, and he approached. I asked him if we worked at the site; he did. So, I asked him about the site, and he walked with us for a while. All the archaeological sites and museums I visited in Greece have staff who watch visitors closely. I don’t know their titles. It’s probably something like Museum Guard or Security Personnel, but I call them all guardians.

The Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sport is the government department that preserves Greece’s cultural heritage. Some rules for entering archaeological sites and museums are clear: You need a valid ticket, bags may be subject to search, stay on the path, don’t touch the artefacts, don’t climb on the rocks, flash photography is prohibited, and eating, drinking, and smoking are not allowed (water bottles are permitted).

Other rules and the reasons behind them aren’t clearly spelled out. For example, posing with museum statues and objects is not generally allowed. Even in “open-air museums” such as the Acropolis and Delphi, posing is closely monitored. At the Parthenon, I saw a guardian scold a young couple and demand they delete a too-romantic photo they’d just taken. One guardian yelled at my husband for standing in the wrong place. Anything resembling ancient religious practices, even an activity as innocuous as meditation, also quickly draws the attention of site guardians. Some guardians are friendlier than others; most are polite and just doing their jobs protecting the site and guests. Some are more knowledgeable than others about the site and its artefacts.

My husband and I walked along the path, accompanied by the guardian, passing the Roman Cisterns and Fountains, Gymnasium, Mithraeum, Lykourgean Fortification and South Pylon (Gate), Bouleuterion (Council House), and Sacred House. Temporary improvements had been made to the path, with careful attention to the rocky, slippery, uneven steps. The guardian explained it was for the safety of a film crew.

The Archaeological Museum of Eleusis sits at the top of the path past the Roman House. We were fortunate that it reopened seven months before following restoration works. It is small but remarkable and houses findings associated with the site.

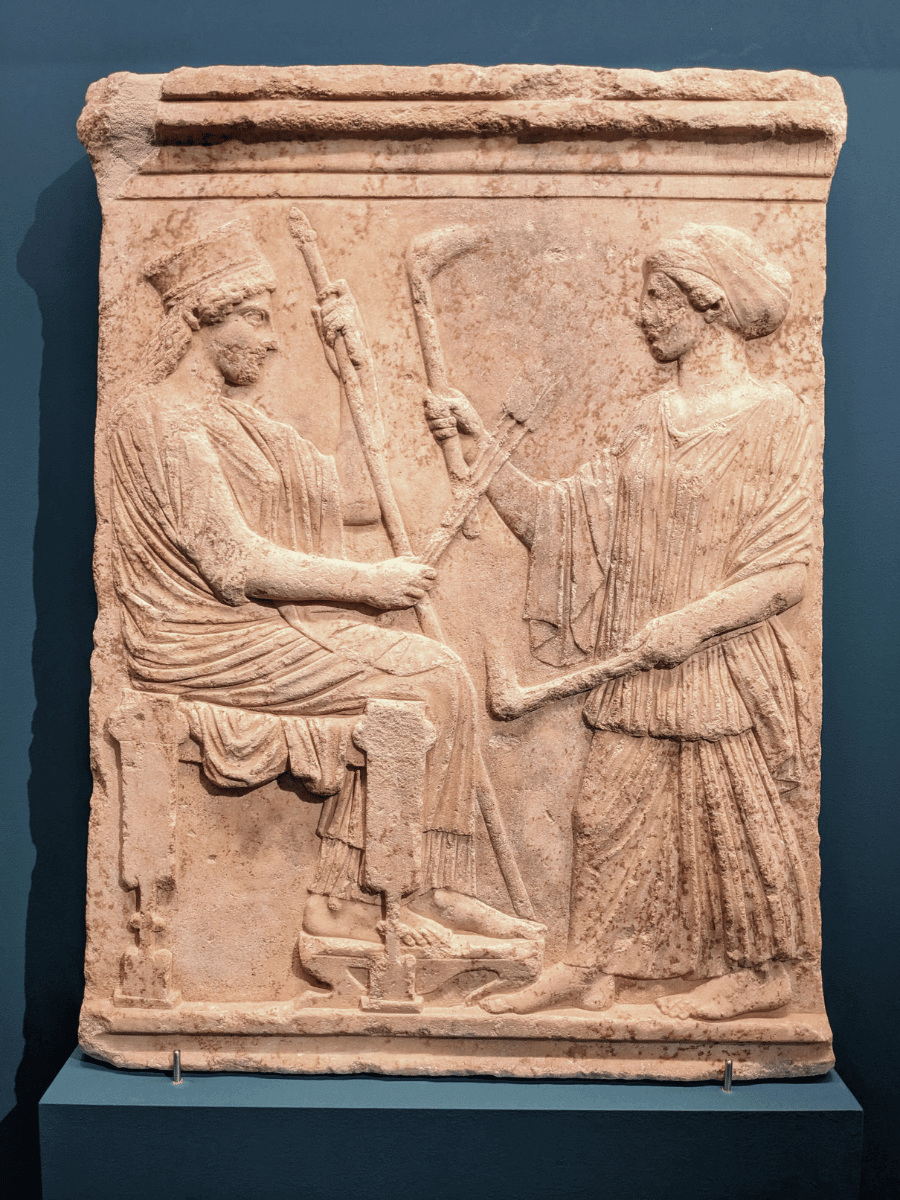

The museum describe this artefact:

“The Eleusinians honour him for training the youths (ephebes) well. The relief depicts Demeter seated on a sacred chest, Persephone standing with torches and Derkylos. The inscription records that the decree stood in front of the monumental gate of the Sanctuary. 319/18 BC.”

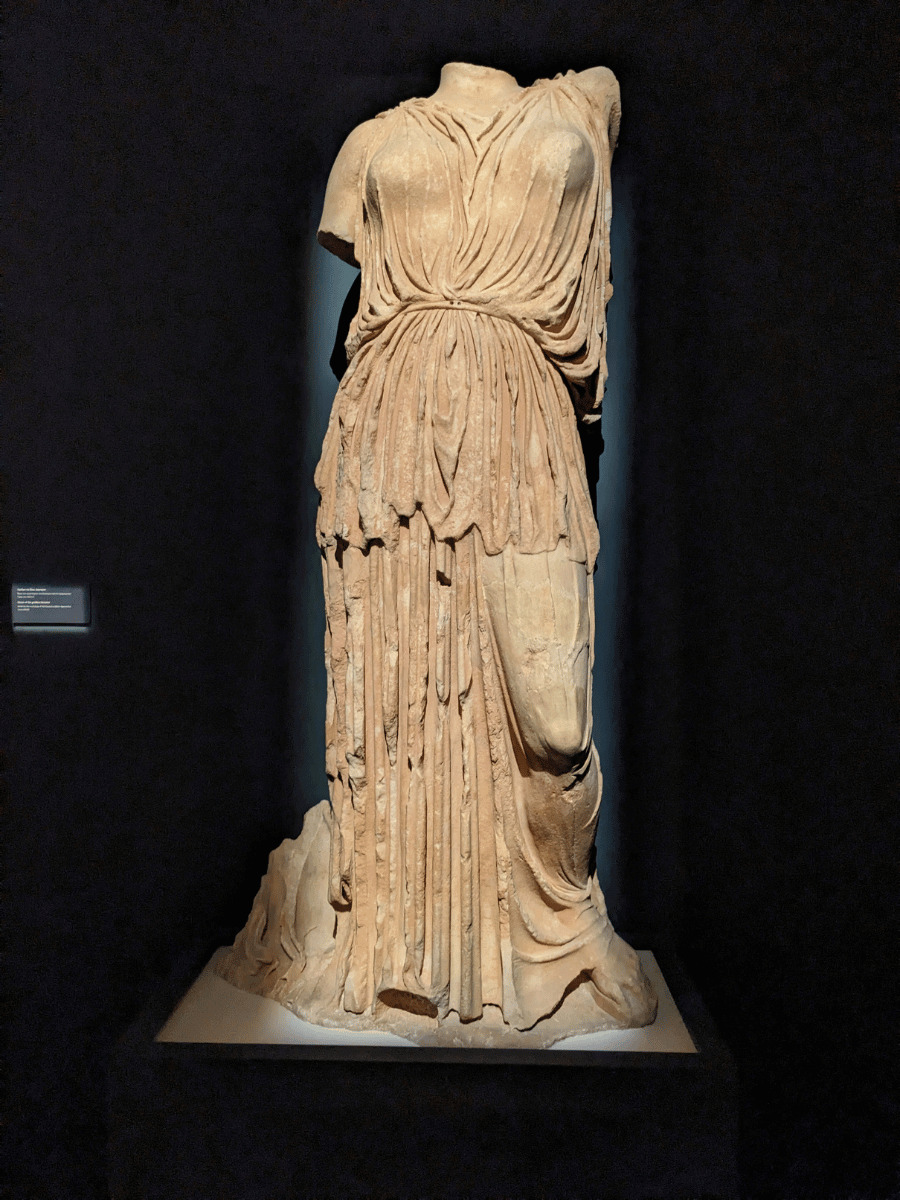

Seeing the “Fleeing Maiden” for the first time was exciting and awesome. She has a magnetic pull and seems ready to leap from the museum’s surrounding stillness. Caught in mid-motion, she is windswept, delicate, and urgent. You can’t help but feel like you’re witnessing something extraordinary–the story of Persephone vivid and tangible.

Who is she? Scholars debate her identity. Here is the museum’s description of her:

“Figure from a lost pediment that depicted the abduction of Persephone by Hades or her ascension from this dark kingdom. It is identified with Persephone or one of her friends, the Oceanids (water nymphs), fleeing fearfully, or with the goddess Hecate, who lights the way back from the Underworld with torches. Circa 480 BC”

On Greeka, the Greek travel agency, this figure is identified as Feugousa Korh, Leaving Daughter, but others believe it is Hekate. In his paper, “The Running Maiden from Eleusis and the Early Classical Image of Hekate,” Charles M. Edwards identifies the Running Maiden with Hekate carrying two torches as she lights Persephone’s return from the Underworld. He argues that this representation of Hekate was standard and found in vase paintings such as the terracotta bell-krater attributed to the Persephone Painter in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Sacred Source reconstructed her as Hekate with Torches.

Along the Sacred Way between Athens and Eleusis were two lakes, the Rheitoi, with the northern lake dedicated to Demeter and the southern to Persephone, marking the boundary between the two cities. The Eleusis Archaeological Museum preserves an inscription from 421 BCE, detailing an Athenian decree to construct a narrow bridge, only 1.5 metres wide, to ensure Demeter’s priests could carry sacred objects on foot. The inscription depicts, from left to right, Demeter, Persephone (with the two torches), a young figure described as a hero, and Athena.

After initiates crossed the bridge of the river Rhetoi on the fifth day of the Elusian Mysteries, known as the Pompe (“procession”), descendants of the legendary Krokos, the first inhabitant of the region, tied a woollen “kroke”, a saffron-coloured ribbon, around the right hand and the left leg of each initiate.

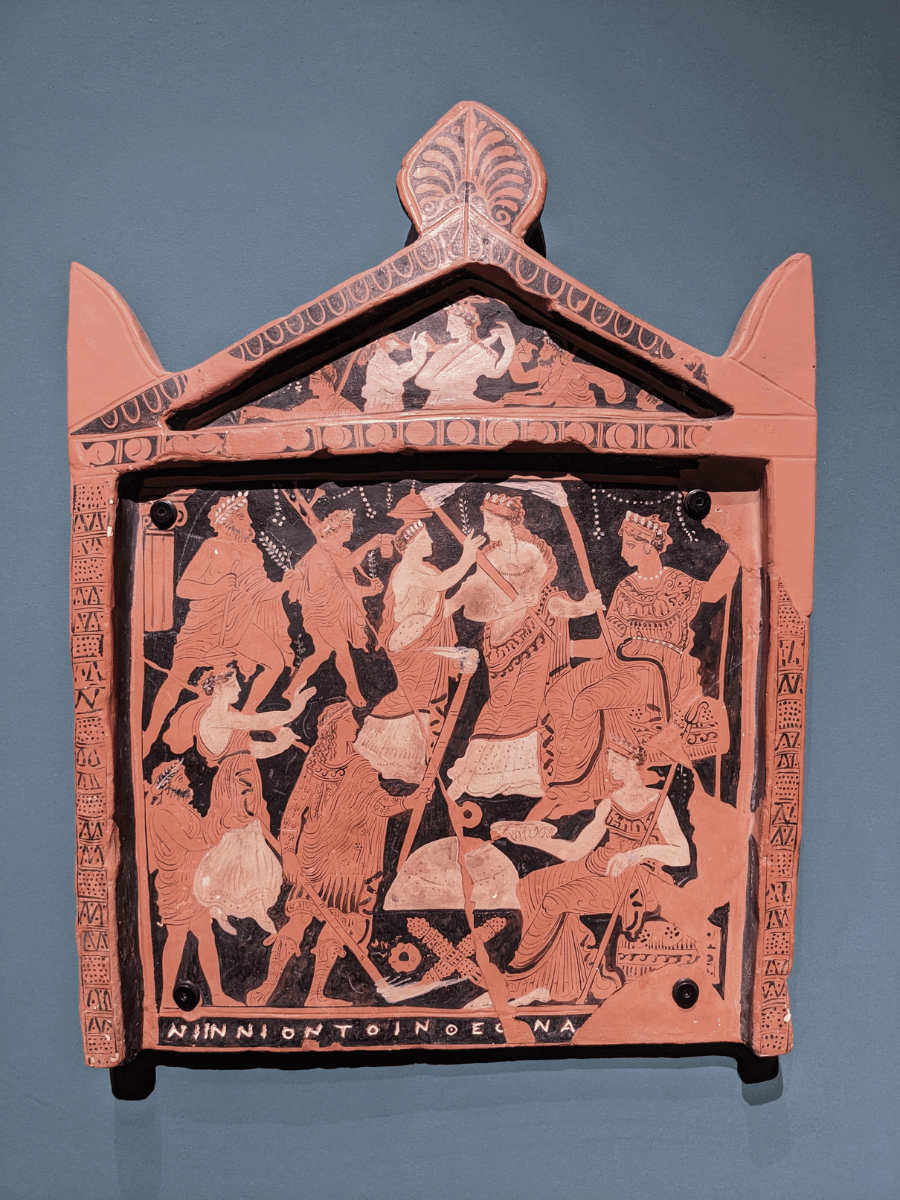

Dedicated to the “two goddesses” by a woman named Ninnion, the Ninnion Tablet is the only known original representation of the initiation rites. Various theories and interpretations of it exist. Does it depict one ritual or two phases, the Lesser or Greater Mysteries, and who are all the figures?

The Ninnion Tablet depicts the god Iacchus leading a procession of initiates to the sacred rites. Demeter appears at the top right, holding a staff and sitting on perhaps the cista mystica, a box containing her sacred items associated with the Mysteries or the Mirthless Rock, on which she sat resting while searching for Persephone, and wept. Persephone, holding two torches, stands to her left. The woman seated below may be a Priestess or Ninnion. Alternatively, she is Persephone, and Hekate is the woman with the torches.

This votive relief depicts the Elusinian hero Triptolemus in his chariot drawn by winged dragons or serpents. It was a gift from Demeter, who also taught him the art of agriculture, and Triptolemus became one of the first men to learn her mystic rites. Demeter charged him with spreading the practice of agriculture. Greece learned to cultivate grain from Triptolemus and worshipped him as the inventor and patron of agriculture.

Persephone, holding the torches, stands behind Triotolemus. The figures behind Demeter are identified as suppliants.

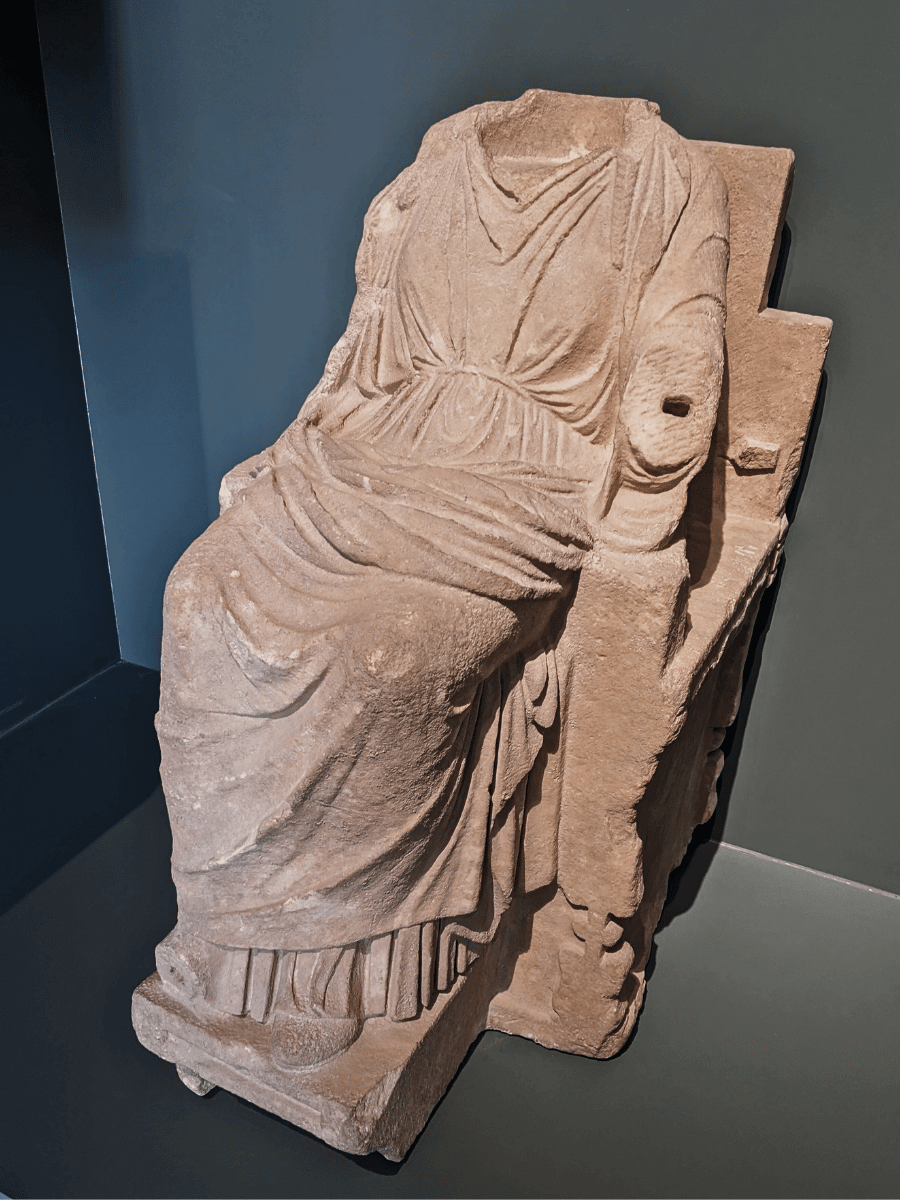

This marble relief is the oldest surviving sculptural representation of Demeter from Eleusis. The museum describes the scene as a seated Demeter welcoming Kore, but the torch-bearer could be Hekate or a priestess.

It is striking to see Kore depicted sitting on her mother’s lap. There are many ways to interpret the myth of Persephone’s abduction. Some see it as a violent kidnapping and rape, others as a metaphor for the seasonal cycle or the patriarchal abduction of the feminine, and still others as a symbolic journey of womanhood and independence. Yet, these tender images remind us that Kore was a maiden, a girl, a daughter under her mother’s care. They evoke a sense of innocence and loss.

This over-lifesize marble statue of Demeter stood alone. She was stunning and powerful.

If you guessed that this beautiful creature with the hair, very demure, is Dionysus, you are correct.

The museum information states:

“One of the two Caryatids that supported the Lesser Propylaea. It represents a priestess carrying on her head the cista, the box in which the sacred objects of the Mysteries were kept and transported. Symbols of the cult are carved on it: sheaves of wheat, poppies and kernoi (characteristic vessels of Demeter’s worship). 1st C. BC”

Back outside

We left the museum and walked down the steps to the Telesterion, the most important building of the Sanctuary. Here, the ritual enactments of the Eleusian Mysteries took place. “Telesterion” means “to complete, to fulfil, to consecrate, to initiate.”

Again, I forgot to take photos.

The Telesterion was a columned, almost square hall with rows of steps along all four sides where up to 3,000 initiates sat. The sacred cult objects were kept in the Anactoron (Holy of Holies), a small rectangular space in the centre that only the Hierophant, the highest priest, could enter. No one revealed what happened beyond “something was done, something said, and something shown.”

I walked through these ruins and sat on the exact steps initiates sat on more than 2,000 years ago. I felt wistful–full of longing and gentle sadness in such a special place, imagining, perhaps remembering, what it once was and what remains.

Along the Processional Way, which continues the Sacred Way, a stepped platform is cut into the east slope of the rock. On a rectangular terrace south of the exedra, foundation traces of a building identified with the temple of Hekate are preserved.

The Ploutonion centres around two shallow caves believed to mark the origins of a primordial cult. The remains of a small temple dedicated to Pluto lie in front of the larger of the two caves. A triangular enclosure with a deep, circular pit, likely used in cult practices, demarcates this sacred area from the rest of the sanctuary. It’s not clear how the caves were used and what rituals were associated with them.

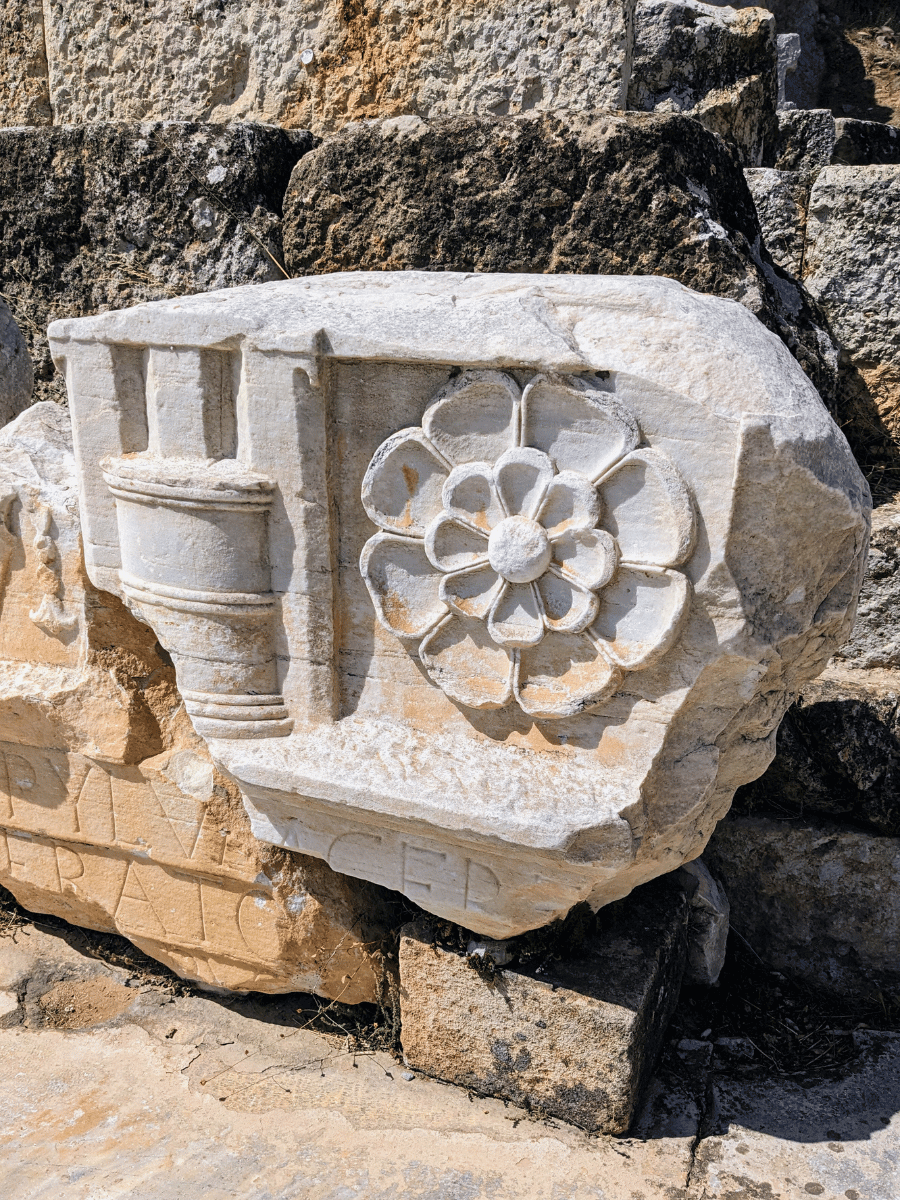

The Lesser Propylaea, a monumental gateway east of the Ploutonion, once served as the main entrance to the Eleusinian Sanctuary before the construction of the Greater Propylaea further north. The Doric frieze was decorated with Demeter’s cult symbols: cistas, sheaves of wheat, rosettes and bucrania.

I visited Eleusis in search of Hekate, only to find she is scarcely acknowledged there. Depictions of a torch-bearing woman are almost always identified as Persephone, with only rare hints that the figure might represent Hekate or a priestess. Even the remnants of her temple are left unmarked, making her presence at the site nearly invisible.

Hekate’s role as a guide and protector during Persephone’s descent and return may be overshadowed by the central figures of Demeter and Persephone in the Eleusinian Mysteries. However, Hekate’s near-invisibility at Eleusis might reflect a deeper resonance with the Mysteries themselves. As the goddess of thresholds and transitions, Hekate often serves as a silent presence, the unseen force that opens the way. In a sense, her role at Eleusis mirrors the initiation process: she is there to guide the initiate into mystery, yet she remains in the shadows, just beyond reach. Ancient visitors would likely understand this subtlety—recognising Hekate in the unseen boundary she guards. Her presence doesn’t need to be marked, for her power lies in the unmarked spaces, in the transition from the known to the unknown that defines the Mysteries.

While Hekate remained elusive, I found Demeter and Persephone everywhere—goddesses outside my pantheon but ones I understood more deeply at Eleusis. Walking through their spaces, I could sense the enduring presence of Demeter, a mother in her bond to Persephone and her relentless pursuit of life’s renewal. And Persephone, more than just a goddess of dual realms, revealed herself as a figure of resilience, embodying the delicate balance between life and death, light and dark. Their myth was visceral, rooted in the earth, weaving together grief and transformation.

While not a central figure in the Eleusinian Mysteries, Athena, who is in my pantheon, has a subtle but notable presence here. It emphasises that her role as administrative protector of Athens extended to Eleusis and perhaps signifies her approval of the Mysteries. Although she isn’t part of the core myth, her presence reminds us that the knowledge sought here belongs to a broader, interconnected web of divine influences.

Thank you for this wonderful description of Eleusis. I have been a devotee of Hekate for many years. I was able to visit her temple at Lagina about three years ago, but have not been to Eleusis. I very much enjoyed your description and photographs of the site and your description of Hekate as a silent, powerful presence.