I dedicate February to Themis, the Greek oracular goddess of justice, divine order, and custom. Last year, I travelled to Greece and was fortunate to visit three sacred sites associated with Themis. This blog is about one of those sites, the beautiful ancient site of Delphi.

Delphi, the oracle of the goddess

Delphi, located on the slopes of Mount Parnassus in Greece, is best known for having been the seat of Pythia, the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo who served as its oracle, the Oracle of Delphi, also known as the Pythoness. The stories of how Apollo acquired the Oracle at Delphi vary.

One popular myth tells that Apollo travelled from his birthplace of Delos, seeking a place for an oracle, and arrived at Delphi as a dolphin, and this is one explanation for the site’s name, from his form as Delphineus, “of the dolphin”. The site was said to have been called Pytho, related to Python, a male chthonic serpent that guarded the site, which Apollo killed to claim it as his oracle. However, there is literary and archaeological evidence that the oracle was originally devoted to the Earth goddess, Gaia. Themis is Gaia’s daughter and was her successor of Delphi.

Delphi shares the same root with the Greek word for womb, delphys. The Suda, a 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, offers that Delphi took its name from the Delphyne, the name of the drakaina, or female dragon or serpent, that Apollo killed. In the Eumenides, Aeschylus omits the slaying of the serpent. His version of the history of Delphi is one of succession in which another Titan, Phoebe, daughter of Earth and sister of Themis, gifted it to Apollo. Whether violent or peaceful, the stories demonstrate a transition to male ownership and the annexation of the wisdom of Mother Earth by the solar god.

Delphi was rededicated to Apollo from about 800 BC, but it had been an important oracle as early as 1400 BC. Gaia and Themis spoke the oracles. She, not Apollo’s priestess, is identified on an Attic red-figure kylix, 440–430 BCE, seated on the tripod, veiled, holding a phiale (shallow bowl) and branch, consulting with King Aegeus. I went to Delphi for Gaia, Themis, and their Pythia, not Apollo.

Visiting Delphi

It was a beautiful, warm, sunny day when my husband and I visited Delphi. It’s a vast area that includes:

- the modern town of Delphi adjacent to the ancient precinct

- the Temple of Athena Pronaia, which, despite its name, is not a single temple but a group of buildings comprising temples and treasuries, and is about 800 m from the main ruins at Delphi

- a gymnasium, which is approximately 800 m from the main ruins at Delphi

- the Castalian Spring, which is about 500 m from the entrance to the archaeological site of Delphi

- the Delphi Archaeological Museum

- the Corycian Cave, once a cult centre of Gaia and later thought to be a residence of Dionysus

We spent much of the day at Delphi and did not see everything. We did not explore the town, the Temple of Athena Pronaia, or the Castilian Springs. As we were leaving, we found the modern fountain close to the street leading to the site. There is little water at the site, and drinking from the fountain and refilling our bottles was wonderful. It’s worth spending the night nearby and giving Delphi two or three days.

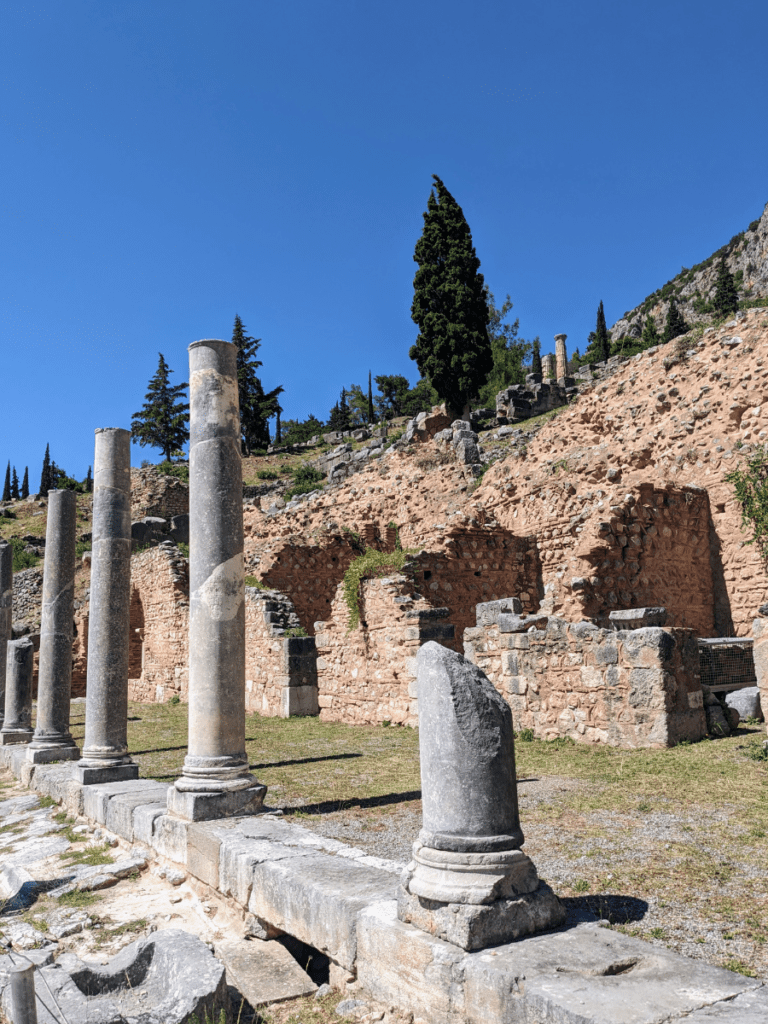

The Roman Agora is the first set of remains a visitor sees upon entering the archaeological site of Delphi. This expansive area was a civic and commercial centre. Visitors could buy statuettes and small tripods to leave as offerings and assembled here for processions.

Legend has it that in his attempt to locate the Earth’s centre, Zeus released two eagles from opposite ends of the world, and they met at Delphi, designating it as the omphalos, “navel of the Earth”. The omphalos, kept in the inner sanctum beside the tripod and bay leaves, was believed to mark the spot where Apollo slayed the Python. It also represents the stone Rhea wrapped, pretending it was Zeus, to deceive Cronus, who had been swallowing all his children to prevent them from usurping him. By the way, Hekate, who was a midwife to Rhea, delivered fake baby Zeus to Cronus.

The original stone is in the Delphi Archaeological Museum. The one shown here is a simplified copy at the site where French archaeologists found it.

There are several so-called treasuries along the slope to the Temple of Apollo. Greek city-states built these to commemorate victories and thank the oracle, whose prophecies and advice contributed to those victories. Treasuries housed votive statues, spoils of war, and a tithe, representing a tenth of the battle spoils. The restored Athenian Treasury, constructed to commemorate their victory against the Persians in the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, stands out as particularly impressive. The metopes of the Athenian Treasury depict the myths of Theseus and Heracles.

The Stoa of the Athenians lies along the Temple of Apollo near the Athenian Treasury. An open-sided, covered porch, an inscription informs us that the “Athenians dedicated the portico and the armaments and the figure heads of the ships that they seized from their enemies” after the Persian Wars.

The Sibylline Rock stands between the Athenian Treasury and the Stoa of the Athenians. The rock is where the pre-Apollonian Sibyl sat and delivered her prophecies. A 1936 site plan of the Sacred Precinct by the French archaeologist Pierre de La Coste-Messelière shows that the ancient sanctuary of Gaia was nearby. I walked through the area, but there were just ruins, and it’s unmarked.

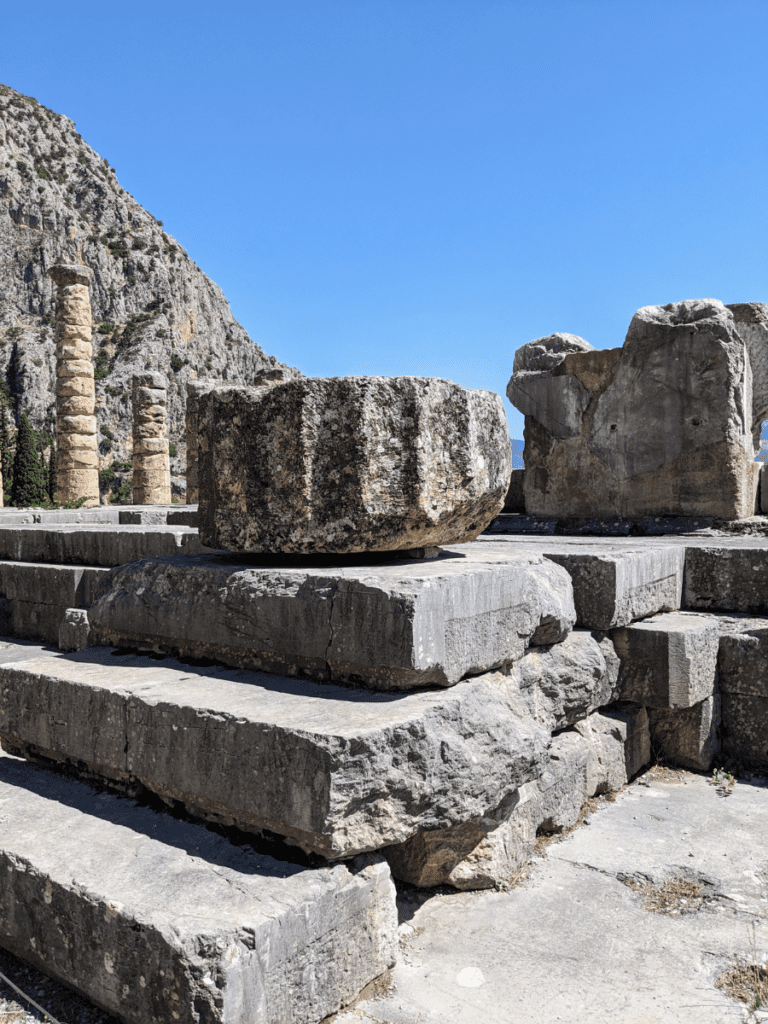

The photo above shows the Serpent Column, the Altar of the Chians, and the front of the Temple of Apollo.

The Serpent Column, also known as the Plataean Tripod, is an 8-metre (26 ft) high bronze column that, together with its original golden tripod and cauldron(both long missing), was built to commemorate the Greeks who defeated the Persian Empire at the Battle of Plataea (479 BCE) and dedicated to Apollo at Delphi. However, it’s a replica. Constantine the Great moved the Serpent Column to his new capital, Constantinople, in 324 to decorate the Hippodrome, where it still stands today.

As my husband and I stood before it, I said to him, “Remember this column. We’re going to see the original one when we arrive in Istanbul in a few weeks.”

Beyond the Serpent Column, on the other side of the steps, is the Altar of the Chians. Dedicated by the people of Chios, the fifth largest Greek island, it was the main altar of the Temple of Apollo.

Then, we finally arrived at the Temple of Apollo.

The Archaeological Site of Delphi is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that draws over 600,000 visitors annually. Many appear to come in motorcoaches from Athens and take a short tour. I’m not fond of crowds, but everyone was polite and friendly. I also found walking along with them and listening to their tour guides informative. If you’re not in a hurry and are patient, you can find moments of solitude and quiet between the tours arriving and departing.

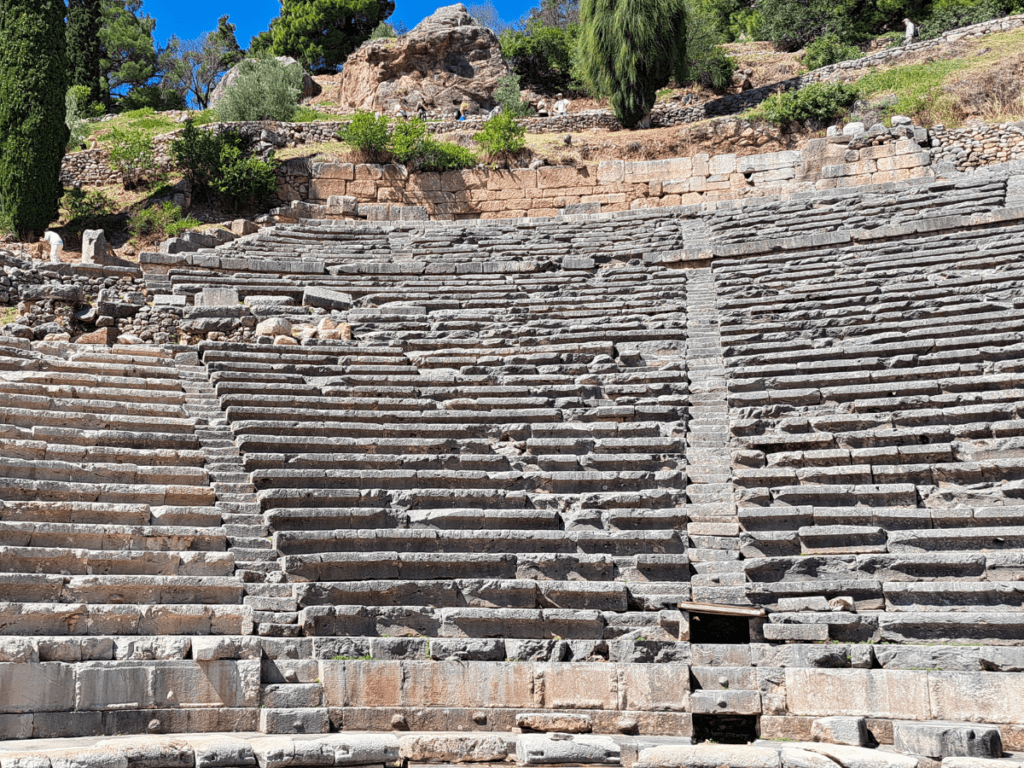

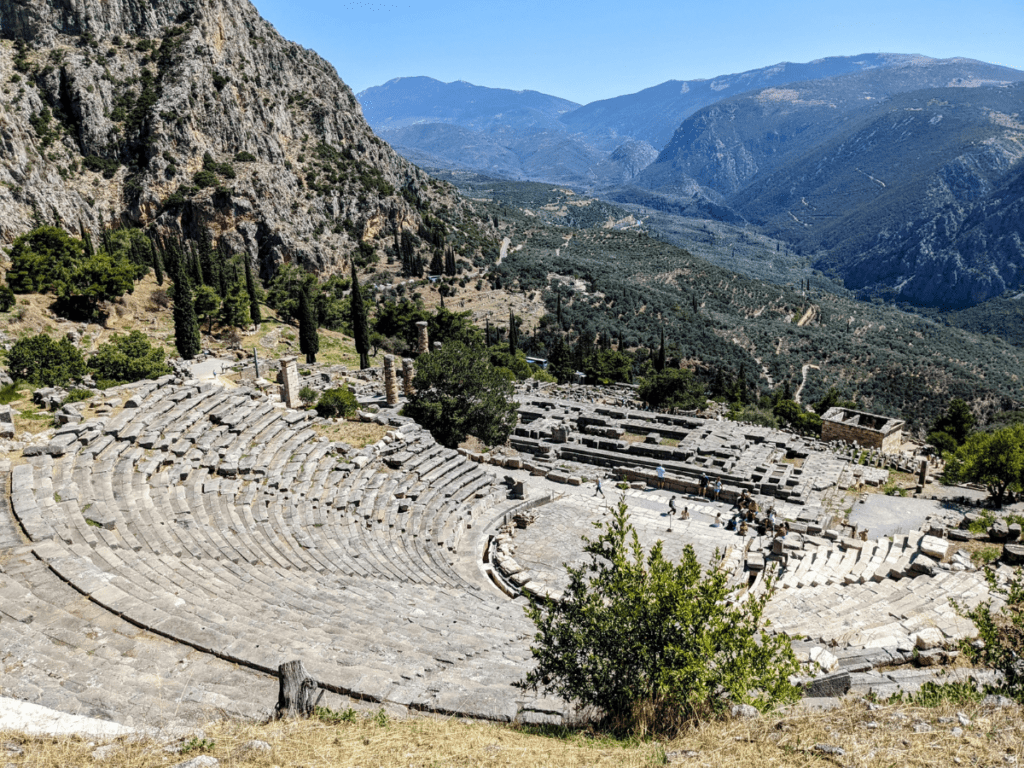

Unfortunately, but understandably, visitors are not allowed to walk into the Temple of Apollo. You can walk close to it, around it, and continue the path up to the theatre and mountain-top stadium. Along the way, there are more things to see and breathtaking views.

According to Greek traditions and writing references, five temples were built at Delphi throughout history, all badly damaged or destroyed by fires, earthquakes, and wars. The fourth temple was the first to Apollo. The exact layout of the temple is unknown, but Greek writers make references to various parts of it, including the inner sanctuary and the chamber where the Pythia sat.

According to de la Coste-Messelière’s site map, there was a sanctuary of Dionysys near the theatre. I didn’t find it; there are a lot of ruins and, again, no signs.

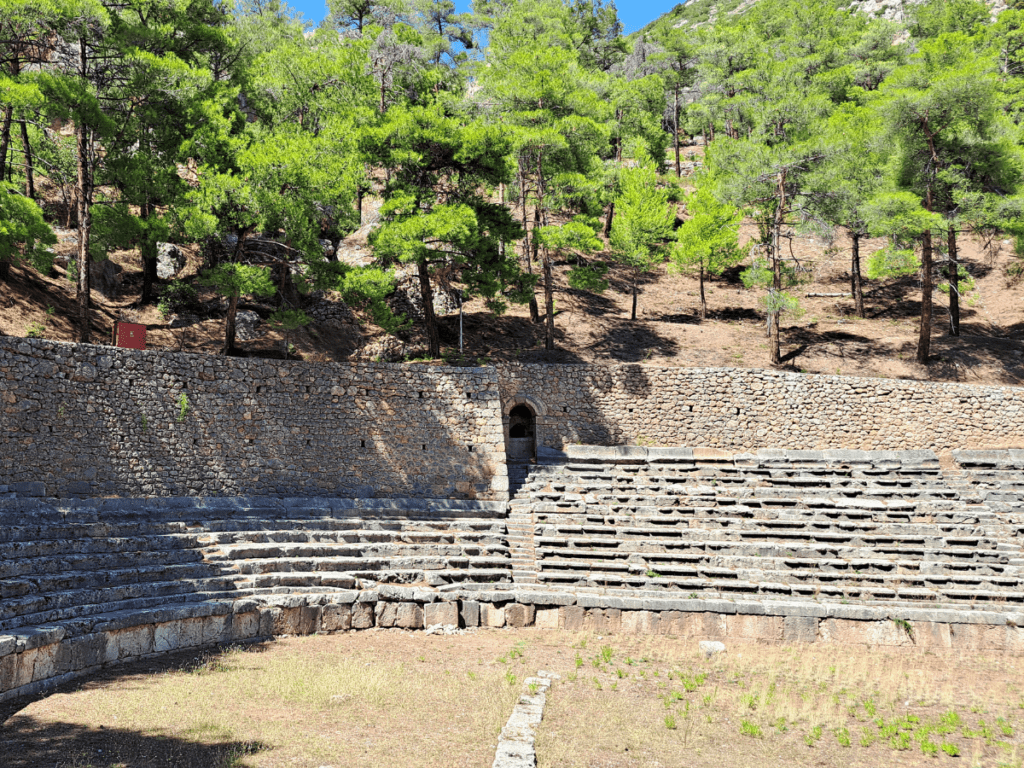

The Stadium of Delphi is at the highest point of the Archaeological Site of Delphi, overlooking the Temple of Apollo. It accommodated 6,500 spectators for events, including the Pythian Games held in honour of Apollo every four years. Second in importance behind the Olympic Games, the Pythian Games included athletic, equestrian, and artistic events such as foot, horse, and chariot races, wrestling, boxing, singing, poetry, and painting for women and girls as well as men and boys.

All the archaeological sites have guardians that watch the tourists closely. They’re there to help protect the site, ensure people stay safe, and assist and answer questions. Rituals are not allowed at any of the sites. Even photos that seem too spiritual, arms raised in front of the temple, for example, are not allowed. The guardians will yell at you from wherever they are and even demand that you delete the photo.

Delphi is special to me because of its oracular connections to two goddesses I am devoted to, particularly Themis, to whom I dedicate all my divinatory and oracular work. When I visited, I was in the first year of Via Carmen Pythia, the Sibyl Training program of the Mt Shasta Goddess Temple. Although we make our commitments at the end of the two-year program, my teacher, Yeshe Matthews, invited me to take advantage of my visit to Delphi and make my vows.

With Yeshe’s help, I found a quiet spot where trees somewhat shielded me from the watchful eyes of the guardians. I sat and meditated, offered a little water from my water bottle, and quietly spoke my vows to Themis. I connected with Themis in the previous days and was very moved as I sat under the tree.

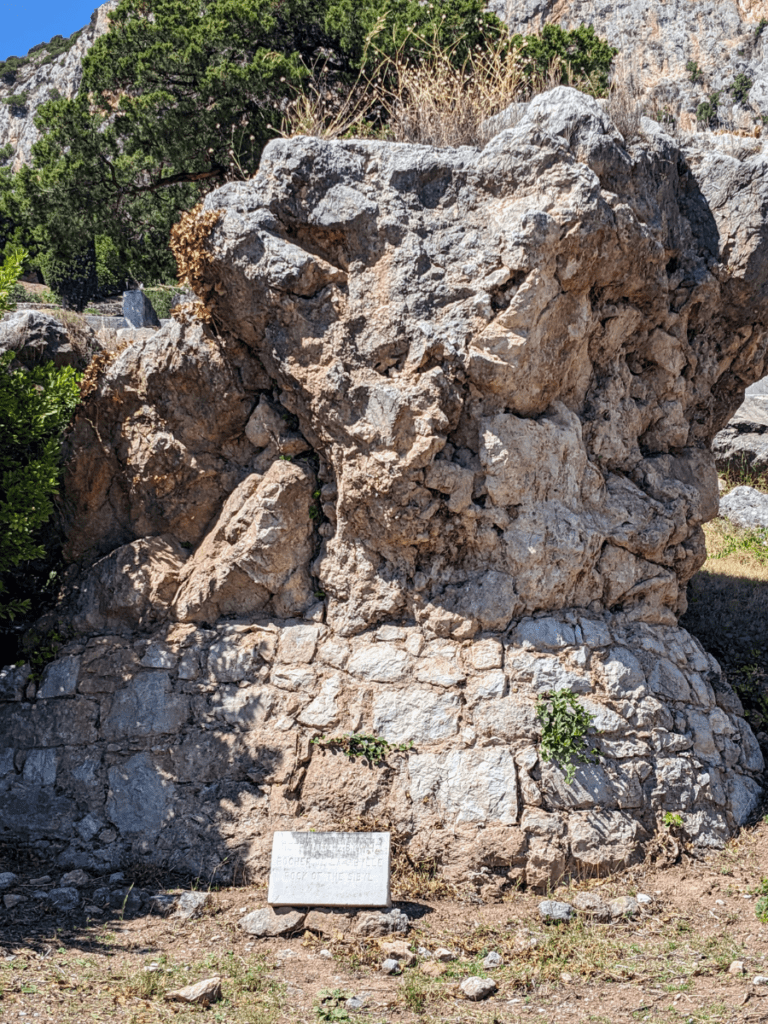

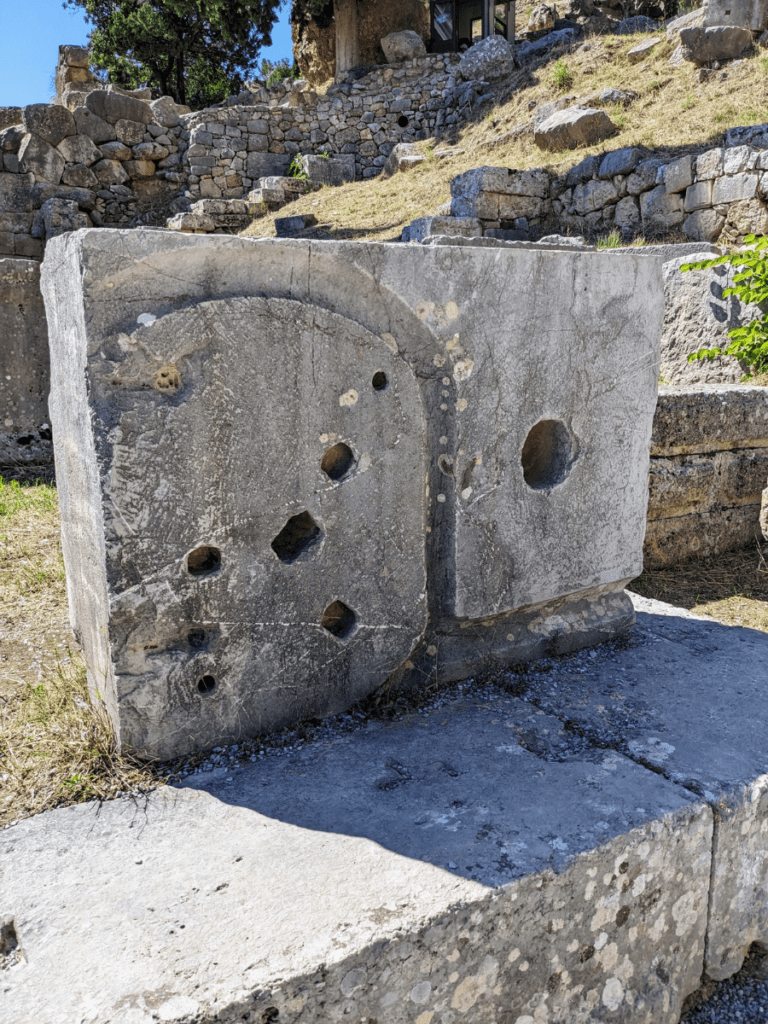

As we walked down the mountain to leave the Sacred Precinct, I noticed the solitary block of limestone pictured above. I had forgotten about this artefact and missed it on the way up, but Themis made sure I saw it on the way down.

According to an article in Ancient World Magazine by art historian Gareth Williams, the French archaeologists who excavated at Delphi found this stone in the adyton, a small, sunken room in the inner chamber of Apollo’s temple where the Pythia sat, perched on a tripod. This stone may have supported the legs of the tripod on which the Pythia sat.

Suppression, abandonment, and rediscovery

Delphi’s prominence endured for centuries, but the site’s influence waned as the Roman Empire rose. The decline accelerated with the spread of Christianity, and by the 4th century CE, prophecy at the Oracle of Delphi had been stamped out. Delphi fell into disrepair, and its treasures were pillaged.

Delphi began seeing visitors again in the 15th century while under the control of the Ottomans. English poet Lord Byron was among the European travellers. He visited in 1809 and left his signature on a marble column in the Gymnasium at Delphi. French poet and author Gustave Flaubert visited in 1851. After the Greek War of Independence (1821-1829), the care of antiquities became a concern, and serious archaeological investigations at Delphi began in the second half of the 19th century.

Delphi is a beautiful place, one of pilgrimage and magic, that I hope to return to. The stones still sing the triumphant songs of its past, and the breeze carries echoes of prophecies whispered by the Pythia.