A group of travellers arrive at a table, unable to speak. Instead, they lay out tarot cards, and a narrator (and the reader) tries to reconstruct their stories from the images. That premise is immediately delicious if you’re a tarot enthusiast… and yet, for me, the reading experience was more admiring than immersive.

This is one of those books I can recognise as clever and important without falling in love with it.

The basic shape of The Castle of Crossed Destinies

Calvino divides the novel into two sections, each with eight tales.

The Castle of Crossed Destinies (first half): the tales are told in the great dining hall of a castle with a deck associated with the Visconti-Sforza tradition

The Tavern of Crossed Destinies (second half): the tales are told in a tavern with the Tarot de Marseille pattern.

Calvino runs the same experiment twice under two different visual languages and two different story-world moods.

The stories literally cross: cards overlap in the layouts, and competing interpretations emerge from the same pattern. In one tale, a central spread is read by two different characters—an alchemist and a knight—who each find their own tale in the shared cards.

Even if the plot beats of individual tales can read like tidy fables, the book’s real ambition is formal: it’s about how stories get made from symbols, and how interpretation behaves when it’s constrained.

In the Castle, everything feels more rarified: a castle, a hushed atmosphere, a sense of high romance and chivalric material. Calvino originally published the first part on its own in 1969 (before the full book appeared in 1973), which helps explain why it can feel like a contained project with a very deliberate internal logic.

In the Tavern, the mood is earthier and more crowded. The stories feel less like courtly romance and more like the messy churn of human life with a sharper edge: paranoia, gender conflict, scapegoating, apocalypse. The setting matters: taverns are where tales cross-contaminate, where you overhear, mishear, embellish, and borrow.

If there’s a “point”, it’s this: the same human impulses look different depending on the symbolic system you’re forced to speak through. Calvino isn’t only telling stories with tarot; he’s showing how tarot (as a visual language) changes what storytelling can do.

A quick note on Italo Calvino

Calvino (1923–1985) is often associated with playful, idea-driven fiction that treats narrative as a structure you can test, bend, and rebuild. This is my first encounter with his work, but he’s known for books like Invisible Cities, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, and Cosmicomics—experimental novels that ask “what if?” questions about the mechanics of storytelling itself. If you’ve read experimental or postmodern literature, you’ll likely recognise the territory.

The Castle of Crossed Destinies is very much in that vein: a semiotic novel (a novel about signs and meaning-making) that asks what happens when you remove ordinary speech and replace it with images that are familiar, charged, and culturally sticky. The result is deliberately self-conscious: the written word isn’t the origin of the story here. It’s the reconstruction of something already said in images. As Calvino himself frames it, these are stories “which the written word tries to reconstruct and interpret.” That gap between image and interpretation is where the book lives.

In his notes to the book, Calvino explains his approach:

“Tarots have inspired a vast tradition of cartomancy based on various interpretations: symbolic, astrological, cabalistic, alchemistic. There are few traces of all this in the present book, where the cards are ‘read’ in the most simple and direct fashion: by observing what the picture portrays and establishing a meaning, which varies according to the sequence of cards into which each individual card is inserted.”

This is important if you’ve seen reviews criticising Calvino for “not understanding tarot.” He’s not trying to do traditional cartomancy. He’s working with the images themselves, their visual content and their combinatorial possibilities. And that’s as valid an approach to reading tarot as any other.

The tarot decks

The Visconti-Sforza / Bembo-style deck (Castle)

If you’re used to Rider–Waite–Smith, these tarot cards can feel like you’ve walked into tarot’s ancestral gallery: gilded, courtly, emblematic. The imagery predates the occult revival and the Golden Dawn influences that shaped RWS, so there’s less psychological interiority and more heraldic formality.

There’s an important complication: no complete Visconti-Sforza deck survives. Multiple historical sets are missing cards, and a commonly cited absence includes The Devil and The Tower, which Calvino himself treats as narratively crucial. The Pierpont Morgan-Bergamo Visconti-Sforza tarot survives at 74 cards, with missing cards including The Devil, The Tower, Three of Swords, and the Knight of Coins.

For a novel that depends on the visual presence of cards, that’s fascinating and a little mischievous. If your edition shows margins where those missing images should be (mine does), you’re left in a strange position: you’re reading a story “told by images” where some of the key images are unavailable.

You can take that in a few ways:

As a literary sleight of hand: Calvino needs the Devil and Tower energies in the narrative machine, whether or not the images exist for the modern reader.

As an invitation to imaginative reconstruction: the missing cards become a gap you’re meant to feel. We have to assume the events of the novel take place before these cards were lost, which creates a temporal tension between the fictional world (where the cards are present) and our reading experience (where they’re absent).

Or as a fair critique: if the project claims to ground itself in the visual authority of the cards, missing visuals expose the limits of the concept. How can we fully engage with stories told through images we can’t see?

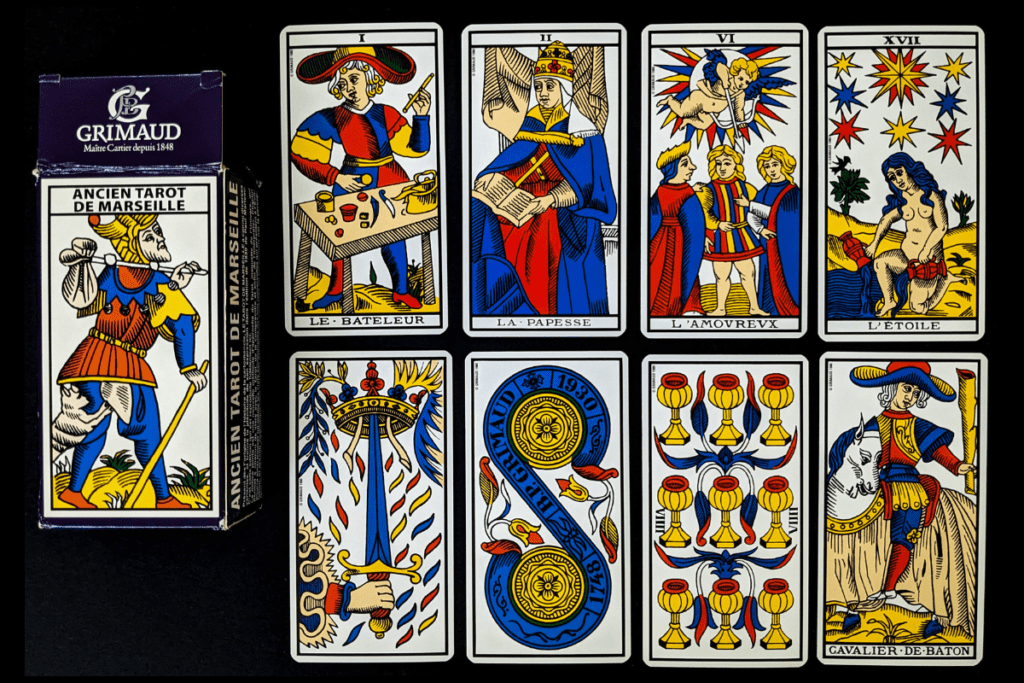

The Tarot de Marseille (Tavern)

The Marseille pattern is later and more standardised: bold linework, emblematic majors, non-scenic pips (no illustrated minor arcana scenes like in RWS). Historically, it became widespread in France in the 17th–18th centuries, and it’s still the backbone of many traditional decks today.

In practice, this matters because the Marseille deck is a more “public” symbolic language: less courtly, less bespoke. The Tavern’s stories feel like they belong to a broader cultural commons, and the reading experience shifts accordingl

My reading experience: good, not gripping

Honestly, the tales didn’t consistently draw me in.

Many of them are built from clean, familiar moral mechanisms, the kind that can feel like “yes, I see it” rather than “I need to know what happens next”. I didn’t often encounter rich character psychology or subtle symbolism. Often, I found myself thinking: Is this it, or am I missing something?

For me, at least, the answer seemed to be no. Death means death. The Devil means the Devil. Your mileage may vary—other readers might find layers I didn’t—but I came away feeling the stories operate more through direct visual logic than hidden depth.

And yet the book kept winning me back on the level of method: the idea of tarot as a storytelling engine, and the narrator’s role as the interpreter who must stitch image into sentence, sequence into meaning. That’s where the real pleasure is (at least for me): not “what does this symbol mean?” but “what does it mean that we can’t stop making stories out of symbols?”

If you’re a tarot reader, you already know this feeling. You’ve sat with cards that could mean three different things depending on where you look first, what the querent just said, or which card landed next to it. Calvino makes that process visible and strange, so that something familiar becomes new and deliberate.

The parts I loved (or at least, the tales I really liked)

“Favourite” is a strong word here, but these are the stories that stood out.

The Tale of the Ingrate and His Punishment: the presence of the Popess (the High Priestess in RWS) and the surprising appearance of Cybele, the Phrygian mother goddess. There’s something satisfying about seeing a pre-Christian goddess muscle her way into a tarot narrative.

The Tale of the Alchemist Who Sold His Soul: that evanescent feminine figure at the end feels more like metaphysics than moralising. Less “here’s the moral” and more “here’s the mystery”.

The Waverer’s Tale: the sharpest ethical point in the book, for my money—that indecision, passivity, and “not acting” aren’t neutral. In a book full of dramatic action, this one quietly insists that not choosing is itself a choice with consequences.

The Tale of the Forest’s Revenge: its cold, timely sense of apocalyptic continuation—machines running when people aren’t there anymore, humans becoming unnecessary. When you remember the book was published in 1973, this hits differently. Calvino was writing ecological and technological dread before they became ubiquitous.

The Surviving Warrior’s Tale: fragile masculinity written as catastrophe, not just personal humiliation. Another one that feels unnervingly current.

The Tale of the Vampire’s Kingdom: the way purity and order collapse into accusation, scapegoating, and mob logic. Watching a community turn on itself because someone needs to be blamed resonates.

I Also Try to Tell My Tale: Calvino stepping forward and the suggestion that writing (and tarot) can give voice to what’s suppressed, with a wink toward psychoanalytic reading. There’s something satisfying about the author acknowledging his own presence in the interpretive act.

What strikes me about these stories is how they keep speaking to contemporary anxieties—ecological collapse, toxic masculinity, scapegoating dynamics—even though Calvino wrote them over fifty years ago. This isn’t necessarily because he was making deliberate political commentary (though he may have been). It’s more that powerful archetypal images naturally resonate with enduring human concerns. The Tower doesn’t only mean one disaster; it means the structure of disaster itself. The cards keep finding new relevance because they’re built to contain multiplicity.

Who is this book for?

This is experimental fiction, not a how-to guide or a book about divination techniques. If that’s what you’re after, look elsewhere.

But if you want:

- a character-driven novel: probably not.

- a book that treats tarot as a narrative technology: yes.

- a literary mirror for what we do when we read cards: building coherence, tolerating gaps, making meaning under constraint—absolutely.

It’s also a good reminder that tarot isn’t only a divinatory tool in culture. It’s a myth machine: a set of images with enough gravitational pull to organise human experience into story. Whether you’re reading cards for insight, for clients, or for creative inspiration, Calvino’s experiment makes visible something we do intuitively and shows both its power and its limits.

While many novels feature tarot as a plot device—mysteries where cards predict murders, fantasy where decks hold magic—Calvino’s approach is unusual. He’s not writing about tarot; he’s writing through it, using the cards as the actual structural engine of the narrative. In that sense, it’s a genuinely unique experiment in what tarot can do as a storytelling form.

A closing thought

I didn’t finish this book feeling enchanted. I finished it feeling alert.

It’s the kind of book that makes you look back at your own practice not to ask whether your interpretations are “right”, but to notice how naturally the mind turns image into narrative, and how much responsibility lives inside that act.

The book is structured as short tales, so you can read one and put it down; it doesn’t demand marathon reading sessions. But it does ask for attention and a willingness to engage with fiction that’s more interested in form than feeling.

Practical note: I read the William Weaver translation published by Harcourt (ISBN 978-0-15-615455-0), a slim 129-page paperback. Multiple editions exist, and the quality of the card reproductions varies. I strongly recommend getting a physical copy rather than a digital or audio version. The margins contain images of the cards being discussed, and they’re essential to the experience. The Kindle sample I saw didn’t include any images.

You don’t need to own the Visconti-Sforza or Marseille decks to read the book, but if you do have them (or find images online), laying out the patterns as you read could be an interesting way to engage with Calvino’s experiment more actively.