As an initiate of Georgian Wicca, I’m no stranger to the Western Mystery Tradition. We cast circles, work with the quarters, and invoke various beings. But I’ve long resisted going deeper into ceremonial magic—the Golden Dawn hierarchies, the Renaissance grimoires, the elaborate Qabalistic correspondences. It all felt too formal, too Christian, too patriarchal, and disconnected from the earth-based practice that drew me to Paganism in the first place.

Recently, though, I’ve been digging past the formal overlay, past the Renaissance reinterpretations filtered through Christian cosmology, back to the pagan roots of these traditions. Many of the foundational ideas in Western esotericism—the microcosm and macrocosm, sacred geometry, elemental correspondences, the journey of the soul—originated not in medieval monasteries or the noble houses of Florence but in ancient Greece and Egypt. They were pagan from the start.

I’ve started with Pythagoras of Samos, exploring why this 6th-century BCE Greek philosopher and mystic might matter to modern pagans, witches, and magicians.

Who was Pythagoras?

Born around 570 BCE on the Greek island of Samos, Pythagoras travelled extensively through Egypt and Babylon, learning from priesthoods and mystery schools. Around 530 BCE, he established a community at Croton in southern Italy—part philosophical school, part mystery cult, and part intentional community.

The Pythagoreans weren’t a casual study group. Students took vows, lived communally, practised dietary restrictions, and observed periods of ritual silence (sometimes for years). Women were full participants, studying philosophy alongside men, which was remarkable for the time. The community shared all possessions in common and maintained strict secrecy about their inner teachings.

Ancient sources describe initiatory grades: outer students (akousmatikoi) received oral teachings and maxims, while inner adepts (mathematikoi) studied the deeper mysteries of number, harmony, and the nature of the soul. This template of graded initiation, oaths of secrecy, communal practice, inner and outer circles, becomes a recurring theme in Western esotericism. The Pythagorean community adapted structures from the Egyptian and Babylonian mystery schools Pythagoras encountered in his travels, then passed them forward to Platonic academies, Hermetic circles, and eventually to modern covens. We’re working within a lineage that spans thousands of years.

Why Pythagoras matters to modern magicians

Number as sacred reality

For Pythagoreans, numbers weren’t abstract concepts but the fundamental architecture of reality itself. The Monad (1) represents pure unity and source. The Dyad (2) brings forth polarity and otherness; it’s the first division that makes manifestation possible. The Triad (3) creates relationship and resolution, the dance of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. The Tetrad (4) grounds this into material reality—the four elements, the four seasons, the four directions, stability and manifestation in the physical world.

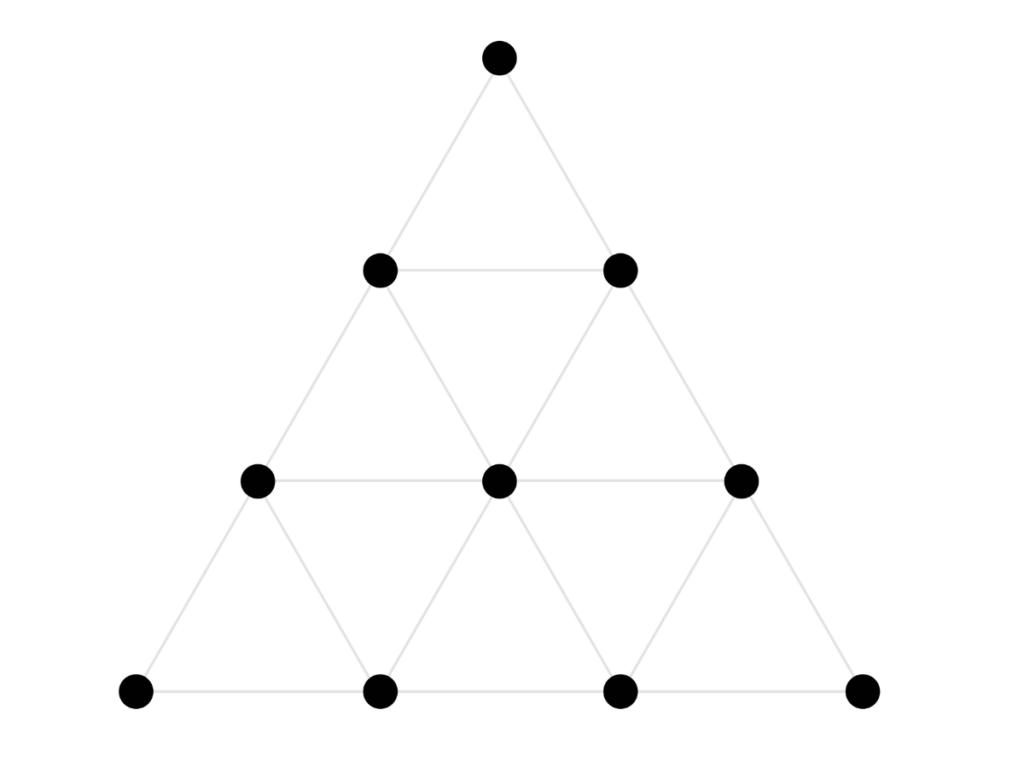

The Tetractys, a sacred triangle of ten dots arranged in rows of 1, 2, 3, and 4, embodies the fullness of creation (1 + 2 + 3 + 4 = 10). Pythagoreans swore their most sacred oaths upon the Tetractys, recognising in it the complete pattern of manifestation from unity through multiplicity into form.

This understanding is that the universe has an inherent mathematical structure, where proportion, ratio, and harmony are the language through which the divine expresses itself in matter.

Harmony as method

Pythagoras discovered that musical consonance arises from simple mathematical ratios: the octave is 2:1, the perfect fifth is 3:2, the fourth is 4:3. This wasn’t just interesting; it was revelatory. It showed that beauty, harmony, and order arise from proportion, suggesting that the cosmos itself operates according to mathematical principles.

From this insight came what later sources attribute to Pythagoras as the “music of the spheres”, the idea that the planets, in their orbital motion, produce a cosmic harmony based on the same ratios found in earthly music. Whether Pythagoras himself taught this concept or whether it was developed by his followers and later elaborated upon by Plato remains unclear, but the idea rippled through Western thought for millennia, influencing medieval astrology, Renaissance magic, and modern physics.

For practitioners, this means that harmony is not merely metaphorical. When ritual flows in right proportion—breath to word, intention to action, element to element—we align ourselves with the fundamental rhythm of existence. Magic works through proportion.

As within, so without: the original teaching

“As above, so below” is usually attributed to the Emerald Tablet (a foundational Hermetic text from late antiquity—more on that another day), but the principle originates with Pythagoras. The idea of the microcosm, that the human being is a miniature universe (mikros kosmos), is fundamentally Pythagorean.

The same ratios, harmonies, and proportions that govern the heavens govern your body and soul. The same numbers that order the planetary spheres order the faculties within you. When you purify and harmonise your inner landscape, you become more cosmic, more attuned to universal order. When you study the patterns of nature and the heavens, you learn the architecture of your own being.

The concept of the microcosm serves as the foundation upon which all Western magic is based. To know yourself is to know the universe. To heal yourself is to participate in cosmic harmony. To act with right measure is to move in step with the spheres.

The tripartite soul

Pythagoreans understood the soul as three distinct faculties that must work in harmony:

- Nous (divine intellect) dwells at the crown. It perceives eternal truths and is capable of direct communion with the divine. This is wisdom, not mere cleverness.

- Thumos (spirited will) is the seat of courage, passion, and drive. Without it, wisdom remains powerless. Untamed, it becomes reckless.

- Epithumia (appetite) governs bodily needs, sensation, and desire. It is not bad, but it requires integration. When appetite rules, the soul is chained to mere sensation.

Right living means establishing proper order: nous governing thumos, thumos restraining epithumia, each in its proper place. This inner hierarchy mirrors cosmic order. A soul so ordered becomes capable of power flowing from alignment.

This is why purification and self-examination matter. They strengthen the rule of wisdom, temper the spirited part, and align appetite with reason. Check yourself before ritual: Is your higher mind clear? Is your will engaged? Are your bodily needs integrated rather than at war with your purpose? A soul in proportion works more powerfully.

The soul's journey through many lives

Pythagorean teaching included metempsychosis, the transmigration of souls. The soul journeys through many lives, perhaps inhabiting different forms (human, animal, plant), slowly learning and purifying itself. This isn’t Eastern reincarnation imported into Greek thought; it was part of the Greek mystery tradition from early times.

For Pythagoreans, this was the ethical foundation of existence. What you do echoes forward, shaping the future dwellings of your soul. Every act of kindness, every moment of honesty, every return to proportion—these polish the soul for its next journey. Through many lifetimes of right living and purification, the soul may eventually transcend the wheel of necessity entirely.

This makes magical practice patient work, measured in lifetimes rather than moons. You’re not seeking perfection in this incarnation but slow attunement across the soul’s long arc.

Practical work with the Pythagorean current

Contemplate the Tetractys

Place the Tetractys on your altar—drawn, painted, or constructed from ten stones or seeds arranged as a triangle. Meditate on how the numbers unfold: the point becomes the line, the line becomes the plane, the plane becomes the solid. Watch creation emerge from unity.

Consider it as a table of correspondences. How might you use it in your magic? What personal associations arise for each number?

Ethical purification as magical hygiene

Adopt a Pythagorean-inspired evening rite. Before sleep, ask yourself:

- What did I do today?

- Where did I stray from right measure?

- What shall I restore tomorrow?

Magic demands clean channels. When we act justly, giving each relationship its due proportion, our will flows true. Think of this as tuning your instrument before the concert.

Work with the elements of the soul

efore magical work, check the balance of your three soul-parts:

- Is your nous (higher mind) clear and receptive

- Is your thumos (spirited will) aligned with your purpose?

- Are your epithumia (bodily needs) harmonised rather than at war with your intention?

Notice which element feels strongest or weakest in you. Where does your practice need focus?

Recognise the patterns in nature

Train yourself to perceive mathematical harmony in the world around you. The spiral of a shell, the branching of trees, the ratios of petals on flowers—these aren’t random. They express the same proportions that underlie music, ritual, and consciousness itself.

Practical observation: Take a walk and count. How many petals are on that flower? (Often 3, 5, 8, 13—Fibonacci numbers.) Trace the spiral of a pinecone or sunflower head; it follows the Fibonacci sequence, which approximates the golden ratio. Notice how tree branches divide: one trunk becomes two limbs, two become three, three become five. The same ratios Pythagoras found in music appear everywhere in nature.

This isn’t just an intellectual exercise. When you attune to these patterns, your magical timing improves. You begin to sense when something is in proportion, when a ritual feels “right,” when the elements are balanced, when the moment is ripe for working. Pattern recognition becomes a practical skill.

Keep a journal of the proportions you observe. Over time, you’ll develop an eye for harmony and discord, for what’s in proper measure and what’s strained. This is the Pythagorean way: study the world to understand yourself, understand yourself to work more skilfully with the world.

Beyond the Christian overlay

Pythagoras was practising Hellenic mystery religion. The cosmology, ethics, and practices all emerge from a pagan worldview, where the cosmos is divine, intelligible, and responsive to human participation. The Renaissance magicians who later worked with Pythagorean ideas naturally interpreted them through their own cultural lens—Christian cosmology, Hebrew divine names, angelic hierarchies. That synthesis produced something powerful and valid in its own right. But it’s not the only way to work with these ideas.

Underneath that Renaissance layer lies something older: a tradition that sees the universe as living mathematics, the soul as an eternal wanderer, and magic as the art of proportion. We can work directly with these Hellenic sources without needing to adopt the later Christian frameworks.

Where this leads

Pythagoras is just the beginning. The thread runs forward through Empedocles (the four elements, Love and Strife), Plato (the World Soul, the Demiurge), Hermetic philosophy, Neoplatonism, and eventually into the magical revival of the Renaissance, but always, underneath, there’s this pagan bedrock.

I’m finding that I can work with ceremonial magic, sacred geometry, and planetary hours in ways that feel natural and aligned with my own practice. These tools come from the Hellenic mystery religion, from pagan traditions that honoured the gods and saw the cosmos as divine.